By Lawrence Robert McCallum, Christchurch, NZ

Robert McCallum, contractor, became a Proprietor of Ground in the Glasgow Necropolis, in late 1844 with the purchase of lair 45 in Compartment Eta for £4/4/-. His son, Robert was buried there in 1847 after only living a few weeks. In 1848 and 1853, the two sons (Malcolm and Horatio Watson) of Robert’s brother Duncan and his wife, Janet Watson were buried there. Later in 1856 another young boy, perhaps the son of an acquaintance or worker, was laid to rest. Eta 45 has no headstone.

On 12 June 1849, Robert at a cost of £18/18/- purchased another lair (108) in Compartment Sigma. His father in law, George McCulloch at the same time purchased the adjacent lair, Sigma 107. Sigma 108 was to become the burial place for Robert in April 1869 and his wife, Agnes McCulloch in August 1880.

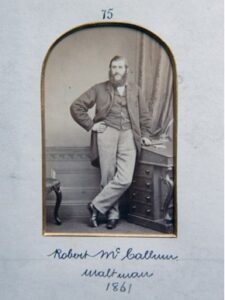

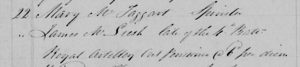

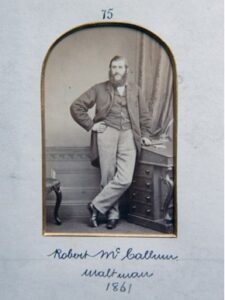

Robert McCallum, Visitor, Incorporation of Maltmen, 1861, Trades House, Glasgow

Life and Family of Robert McCallum

Robert was the eldest son of Malcolm McCallum and Anna Sinclair. He was born in the parish of Glenorchy and Inishail, Argyll in 1818 and came with his family down to Glasgow about 1824 (when his first sibling was born in Glasgow rather than in Argyll). Malcolm McCallum came from Clifton, Tyndrum, the lead mining village to the north of Loch Lomond. The Sinclairs lived nearby in the village of Kinachreachan with both areas part of the lands of the Earls of Breadalbane. While Malcolm may not have done much lead mining, his father probably did, with the top level shaft into the side of Sròn nan Colan being referred to as “McCallum’s Level”. In 1741 a vein of lead ore was discovered at Tyndrum and was mined intermittently, with shafts dug horizontally into the side of the hill, ore brought down using ponies, smelted at Tyndrum and taken out via Loch Lomond to Glasgow and elsewhere (Stephen Moreton, “Lead Mines of Tyndrum” 2015, Northern Mining Research Society, British Mining No. 99).

For this story, the key point is that Malcolm knew how to handle stone and could use that skill to become a contractor and quarrier in the growing city of Glasgow. Compared to thousands of Gaelic Highlanders, he could earn a living to house and feed his growing family. In Glasgow he did start as a spirit dealer (cash flow) but eventually moved on in terms of respectability and income to become a contractor. In 1844 Malcolm, by purchase became a Maltman, in the Incorporation of Maltmen, one of the fourteen trades that made up the Trades House, in the Trades Hall, 85 Glassford Street, Glasgow. He was also a member of the Duke Street Gaelic Church and resided nearby at 18 Burrell’s Lane (running between High and Duke Streets). He purchased a lair in St David’s Ramshorn Church Burial Ground and is buried there with his wife and some of his children, dying in 1850.

Robert followed what his father had done and took it several steps further with the purchase of property, becoming the Visitor (Chairman) of the Maltmen in 1861 and then a Deacon on the convening committee overseeing the Trades House in 1862. In 1851, having already moved from spirit dealer to contractor he purchased land with houses, yard and stables on the corner of Duke and Barrack Streets. From 1854 till 1898 the Glasgow Postal Directories referred to it as “McCallum’s Buildings”. Later that year he borrowed £1200 from The Friendly Society of the Ministers of the Relief Synod. He had already married Agnes McCulloch back in 1842 and the first of thirteen children was born in 1844. All the children lived through to adulthood except Robert who died after six weeks in 1847. A later son was also called Robert. It seems he was on good terms with his father-in-law, George McCulloch, who perhaps mentored and advised his son-in-law. They jointly acquired a property on the Gare Loch, Aikenshaw at Rahane.

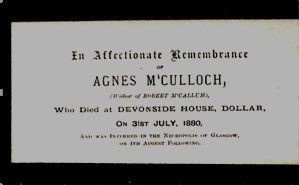

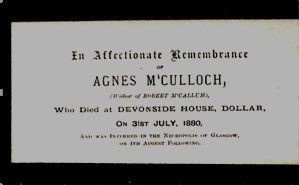

Agnes McCulloch, Mrs Robert McCallum, 1824-1880

In 1854 Robert set out his will in the form of a Trust Disposition and Settlement. It included a statement whereby his wife, Agnes, declared her entire satisfaction with the provisions set out. By the time of his death on 25 April 1869, at 129 Barrack Street, Glasgow, at the relatively young age of 51, Robert was a moderately wealthy man with an estate of £5833 10s 1d (between half a million and ten million pounds in today’s money, depending on the measure used).

He had a substantial base down below the Necropolis on the Barrack Street/Duke Street corner with several rental houses and shops along with his contracting yard and family home. He then also had two houses overlooking the Gare Loch. The first was Aikenshaw, a villa set on three acres at Rahane (along with several cottages which were rented out). Rahane lies between Rosneath and Gairlochhead on the western side of the Gare Loch, the arm of the Clyde reaching up past Helensburgh. The second was Summerhill, at Shandon on the opposite side. Again there were rented cottages with the house, which was up the hillslope behind the Free Church and near where the jetty was built in 1886. The natural beauty and serenity of the Gare Loch could not be in greater contrast to Duke Street, with its prison, cattle market, crowded tenement buildings, noise and grime. No wonder some of his children had the Gare Loch rather than Glasgow put on their gravestones out in Australia and New Zealand.

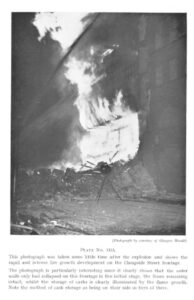

Robert was very much both a quarrier and a contractor. The 1855-56 Valuation Roll shows Robert McCallum, Contractor, Glasgow as the tenant/occupier for the Auchinstarry Quarry (whinstone) just south of Kilsyth and near the Forth to Clyde Canal and Cumloden Quarry (also referred to as Crarae) on Loch Fyne, a sea loch leading to Inveraray in Argyll. From the quarries Robert brought the stone by canal and sea to Glasgow for paving its streets.

Aikenshaw, Rahane, Gare Loch, Christmas 2004

Robert’s Death in April 1869 and the McCallum Family in the 1870s

When Robert died on 25 April 1869 his contracting equipment and draught horses were soon sold. His second son, George is listed in the 1871 census as a contractor but like most of his siblings, they did not have the drive and acumen for business like their father. The McCallum family shifted out of 131 Barrack Street and were spread around, with George and his sisters, Jeannie, Agnes, Susan, Maggie and Alice living at Dunchattan House (off Duke Street, Dennistoun), mother Agnes and children Annie Sinclair, Duncan, James and William living at Summerhill, Shandon and Robert at boarding school in Dollar, Clackmannanshire. About 1875 (after the death of her mother, Jane Thomson McCulloch in August 1874 in Glasgow), Agnes McCulloch McCallum moved to live in Devonside House in Dollar, dying there 31 July 1880. Summerhill was sold but the Barrack Street/Duke Street properties were retained as an income stream for Agnes.

By the 1881 census and the family were clustered at Aikenshaw with Malcolm operating as the head of the family. George was away in Iowa but about to return and sail for Melbourne. Jane, Agnes, Margaret, Susan, Alice and William were with Malcolm. Robert was over at Fendoch Farm, Crieff while the twins, Duncan and James McCulloch were at boarding school in Lancashire, England. Ann Sinclair was visiting a Peter McCallum and his family at Springfield House, Helensburgh. Ann was always a little different to the other siblings, being born in Edinburgh rather than Glasgow or Shandon.

Bereavement Card for Agnes McCulloch, widow of Robert McCallum and buried in the Glasgow Necropolis

Le Mars, Plymouth County, Iowa: on the Prairie

In 1880, two of the children of Robert and Agnes, George and Robert McCallum, sailed on the S.S. California from London to New York and then by rail via Chicago to north-west Iowa. Plymouth County was the focus of a colonization experiment by William B Close and his brothers in the period 1877-1890. Described in “Gentlemen on the Prairie” by Curtis Harnack (1985, Iowa State University Press) it was an attempt to transpose the culture of the British gentry to the Iowa prairie. A colony was set up near the main town, Le Mars. Elgin Township (the county was split into twenty-four townships, each six miles square) where George and Robert were located at the time of the 1880 census is to the north of Le Mars. There was a high dropout rate unless marriage to a local girl occurred and most, like George and Robert returned to easier locations to live their lives.

Robert McCallum (right) at Fendoch Farm, Crieff, Perthshire, c1881 drinking whisky with some friends.

Emigration of Robert’s Family to Australia and New Zealand

After the death of their mother, Agnes on 31 July 1880, all the McCallum children gradually moved to Australia and New Zealand. George and Robert returned from Iowa and George with his sister, Annie Sinclair were the first to depart on 24 January 1882, on the Loch Lomond, a sailing vessel, for Melbourne, Victoria. The children were perhaps attracted to Melbourne, as their uncle, Sir James McCulloch had established himself there in 1853, becoming premier of the colony of Victoria and being knighted. Two uncles on the McCallum side, Duncan and Malcolm had also gone out at the time of the gold rushes. Duncan was a horse dealer in Melbourne, died 1877 but his wife and six daughters were still there. Malcolm became a stage coach driver in western Victoria and lived with his wife and family in Hamilton. An aunty, Jessie, who married William Russell, horse dealer, also moved to Melbourne and then Dunedin and Christchurch, New Zealand.

Viewing the twelve McCallum children, here is where they moved to and were laid to rest.

Malcolm c.1844-1907 – 1881, at Aikenshaw on the Gare Loch; 1889, Invercargill, NZ; 1890, with his brother Robert he owned Woodstock Farm, near Gore, Southland, NZ; 1894 sold Woodstock Farm and moved to Tauranga in the North Island along with brothers, Robert and William and sisters Margaret and Susan; 2 May 1907, died at his residence, Glengore, aged 63 and was buried in Tauranga Presbyterian cemetery. There is no headstone; estate of £1385.

George c.1847-1889 – After Iowa, and sailing to Melbourne, he moved with his sister Annie Sinclair, to Paynesville, Gippsland, eastern Victoria; worked as a fisherman on nearby Raymond Island, sending fish to the Melbourne market; drowned in McMillan Strait between Paynesville and Raymond Island on the night of 9 December 1889, after drinking in Cox’s Hotel and rowing home on his own. He was found next morning floating among the reeds. After an inquest he was buried in nearby Bairnsdale Cemetery, with his headstone stating he was “of Gare Loch, Scotland.”

Jane Thomson 1848-1918 – After time in Melbourne and Invercargill, Jane went to Adelaide, with her sister Alice; 1902 in Port Adelaide, South Australia, married William Whyte, a Scotsman from Kinross who had been out since 1853 and was successful with pastoral leases and a grocery company. Jane was his third wife and he lived till age 99; Jane died 10 October 1918 at Wattle Street, Unley, and was buried in West Terrace Cemetery, Adelaide, aged 67. There is no headstone.

Ann Sinclair c.1850-1934 – Ann sailed on the Loch Lomond with her brother George in 1882; They both went to Paynesville, Gippsland, Victoria where she married John Joseph McKinley, the local school teacher; she then called herself, Annie St Clair McKinley (perhaps as her husband was Roman Catholic); Ann was a sewing teacher before having three children, two girls and a boy; she moved with her husband as he was appointed to different country schools and then to Black Rock, Brighton, Melbourne on Port Philip Bay; her husband died 1917 but Ann lived on till 1 September 1934 in a house she called ‘Aikenshaw’; the family were all buried in Brighton Cemetery, Melbourne.

Agnes Whitelaw 1854-1893 – Agnes came out to New Zealand in the early 1890s, staying at Gore, Southland with her sister Alice; she died there 18 July 1893 and was buried in Woodlands Cemetery, a beautiful rural cemetery south of Gore, with a large white marble headstone.

Agnes Whitelaw McCallum 1854-1893

Susan Renwick 1856-1937 – Named after the first wife of her uncle, Sir James McCulloch, Susan came out to New Zealand in the 1890s and lived with her sister Margaret Miller in Woodlands, a large house near Tauranga; around 1914 they both moved to Takapuna on Auckland’s North Shore; 17 April 1917 she married Alexander Snodgrass Patterson, the son of Scottish emigrants living south of Dunedin. Alexander, through his mother was related to the McCulloch family. Susan died 25 February 1937 and was buried in O’Neill’s Point Cemetery, Bayswater, Auckland, NZ.

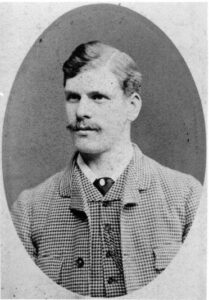

Robert 1859-1924 – Robert was back in Scotland when his mother passed away, being at Fendoch Farm, Crieff in the 1881 census; 1887 he was photographed in a cricket team at Narrabri, northern New South Wales; 1890 Robert was with his brother Malcolm at Woodstock Farm, Southland, dealing with rabbits and raising sheep; 2 November 1895, having moved up north he was engaged to Kathleen (‘Gipsy’) Walker whom he married in November 1897, at Ellerslie, Auckland; they had a daughter, Agnes Kathleen and son Robert McCulloch; after time in the Bay of Plenty near Malcolm the family moved back to south Auckland where Robert was a land agent and farmer at Mauku; 1919 -1923 Robert was the proprietor of the Ventnor Private Hotel at Devonport, Auckland; February 1924 he and his wife purchased the Glenalvon Private Hotel, Waterloo Quadrant in central Auckland; November 1924 Robert died and was buried in Purewa Cemetery, with a polished red stone obelisk “In loving memory of Robert McCallum of Gare Loch, Scotland.”

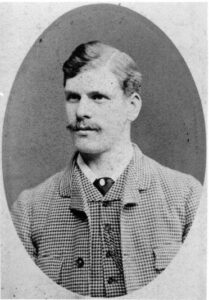

Robert McCallum 1859-1924

Margaret Miller 1861-1949 – Margaret came out to New Zealand in the 1890s and settled at Tauranga with her sister Susan; by 1911/12 her household was sold up in Tauranga and she moved to Takapuna on Auckland’s North Shore; 3 March 1928 she married a retired farmer, Edward George Roper and they lived on Waiheke Island in the Hauraki Gulf, near Auckland; Edward died 1932 and Margaret moved back to Takapuna, dying there in 1949; her ashes were scattered at Waikumete Cemetery, Auckland

Alice Willox Blackley 1863-1931 – Alice came to New Zealand in the early 1890s and lived with Malcolm at Woodstock Farm near Gore; 27 December 1892 she married George Tod at Woodstock Farm. George was a Scotsman from Kinross and a local auctioneer; they had a daughter, Agnes McCulloch; about 1894/95 the family moved to Adelaide, South Australia where George set up business as ‘wool expert’; Alice’s sister Jane Thomson was married in their house at Semaphore, Port Adelaide in 1902; 3 January 1931, Alice died and was buried in West Terrace Cemetery (there is no headstone remaining); George Tod died May 1945 in Adelaide.

James McCulloch 1865-1936 – In the 1881 census, James and his twin brother Duncan were at Alston College in Lancashire; James became an engineer and is likely to have followed his brother to Broken Hill in western New South Wales; 6 April 1903 James married Emma Osborne Davey, a widow from Adelaide, South Australia; they had one son born in Semaphore, Port Adelaide who only lived a few months and was buried in Sydenham Cemetery, Christchurch, NZ; James had problems with alcohol and in 1906 was remanded for assaulting his wife; 7 August 1915 his stepson, Allan Osburne Davey was killed on Chunuk Bair at Gallipoli with the NZ Forces; 24 December 1918, his wife, Emma died and was buried in Sydenham Cemetery; 1921 James married Lucy (Edith) May Cooling in the Christchurch Registry Office and they had four boys and two girls; James died 10 December 1936 and was buried in Bromley Cemetery, Christchurch.

Duncan 1865-1933 – Following time at Alston College, Lancashire (1881 census), by 1887 Duncan had completed an engineering apprenticeship with James Milne Ltd, Edinburgh; from March 1889 to April 1890 he worked as an engineer on coastal shipping around south-east Australia; on 26 August 1895 he married Josephine Laura Pilgrim in Broken Hill, NSW. Josephine was born in Laura, South Australia and her parents came from Suffolk, England to Adelaide in 1850. Her father was a stone mason; Duncan worked as a foreman for Broken Hill Proprietary Ltd in the booming silver mining town; when they left for Christchurch in late 1899, Duncan was given a gold medallion from his fellow foreman with “For Auld Lang Syne” on the reverse; two boys were born in Broken Hill and three daughters and two sons in Christchurch; with his brother James, Duncan worked in the Railway Workshops, shifting to Te Papapa, Auckland in 1919; Duncan died 9 April 1933 aged 67 and was buried at Hillsborough Cemetery, South Auckland

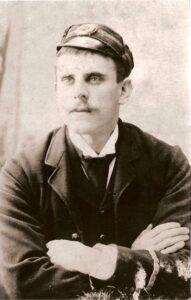

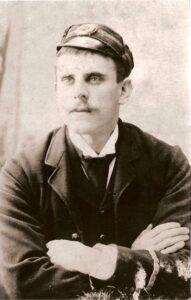

Duncan McCallum, wearing his engineers cap

Medallion on leaving Broken Hill, NSW

Duncan, Josephine and baby Robert James McCallum, South Broken Hill, NSW c1896

Duncan (right back row) and wife, Josephine (second from right front row) at a country wedding at Leeston, Canterbury, New Zealand, 1909

William Thomson 1866-1937 – William moved to New Zealand in the 1890s and went farming at Waihola (near where the Pattersons, his sister Susan Renwick’s husband lived) in the South Island; he then followed his brothers and sisters to Tauranga; from 1914 -1925 he was a drover based in Gisborne over on the East Coast of the North Island where the bush was being cut and burned and sheep and cattle stations were expanding; in 1927 he married Laura Louisa Margaret Tobin in Takapuna, Auckland. Laura’s parents had taught in Native Schools and Laura was elected to the Polynesian Society in 1926 as a noted Māori scholar and fluent in the language; the couple lived on Waiheke Island with William dying in 1937, aged 71 and was buried in O’Neills Point Cemetery, Bayswater, Auckland; Laura died in 1962.

Robert and Agnes’s burial place in the Glasgow Necropolis

Final Rest in the Glasgow Necropolis

Robert and Agnes would have found it hard to comprehend where their children dispersed to. None of his sons took over his flourishing contracting business and while they reminisced of the Gare Loch, the houses of Aikenshaw and Summerhill were eventually sold along with the Duke Street/Barrack Street properties.

Robert and Agnes are both buried in lair 108 in Compartment Sigma, looking down over the Glasgow where they had made their home and living. “He that believeth on the Son, hath everlasting life.”

All photographs from the author’s personal collection.

![This lovely family photograph was taken to mark Margaret McMillan’s 21st birthday on 31st December 1952. She stands in the centre of the back row flanked by her father John and her cousin Kay. At the far right is her brother Ian with his wife Jane McIntosh seated in front of him. Their son John, almost two years old, is sitting in the middle of the front row between his grandmother and great grandmother. [photo provided by Laura Middleton]](https://www.glasgownecropolis.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Margaret-McMillans-21st-birthday-large-web-300x234.jpg)