Alexander Mackenzie

Alexander Mackenzie and his cast iron Monument, Glasgow Necropolis

Alexander Mackenzie Monument

1.0 Background

The Memorial to Alexander Mackenzie sited in Compartment Upsilon in the Glasgow Necropolis is a unique cast iron creation with memorial stone insert. The inscription identifies “Alexander Mackenzie, merchant, Glasgow, died 31st January 1875, aged 62 years; Alice Melrose his wife, died 4th January 1900, aged 82 years”, and “other family members are buried here.”

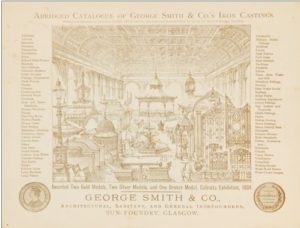

The monument was cast by the Sun Foundry of George Smith and Company as an assembly of parts and is marked with their company details.

Alexander Mackenzie Monument – Sun Foundry Mark

This Memorial has long been recognised as an important piece of Scottish architectural ironwork from a famous Scottish firm. It is now apparent that the connection between Alexander Mackenzie and the Sun Foundry of George Smith and Company went well beyond the supply of this monument. This discovery significantly increases the significance of the monument.

2.0 Significance

2.1 Context

Scottish foundry companies were the leading architectural iron founders in the world. From the establishment of Carron in 1759, the invention of the hot blast in 1828 and the discovery of black-band ironstone in 1804 all the ingredients were in place for rapid development.

The earliest Glasgow architectural ironwork firms started in 1804 with the arrival of the Phoenix Foundry. From this firm began McDowall Steven in 1834. Many other firms grew up on the back of the increasing demand for sanitary castings and so the appetite for decorative ornament increased. The arrival of Saracen in 1850 marked the start of a new phase, and from these works sprang the Sun Foundry of George Smith, the Lion Foundry of Kirkintilloch and a host of other firms.

The industry peaked in Scotland around 1890 but many firms survived into the mid 20th Century.

The Necropolis has dual designation as a designed landscape and a Category A asset.

Category A buildings are:

• Of national or international importance, either architecturally or historically;

• Largely unaltered; and

• Outstanding examples of a particular period, style or building type.

Category A accounts for around 8% of the total number of listed buildings in Scotland.

As a designed landscape it is recognised as an asset which is outstanding as a work of art, historical, architectural and scenic value.

In terms of cultural significance, in summary per the Burra Charter framework ; See: https://www.historicenvironment.scot/archives-and- research/publications/publication/?publicationId=befdca67-7782-4aee-8649-a5c300ab4cdf

2.2 Aesthetic value

The design of the memorial is a unique assemblage from the firm of George smith and Co, Sun Foundry. The style is Victorian, or Revival Gothic, redolent of church architecture of the period. George Smith trained as a pattern maker alongside his brothers and in execution, the work of the Sun Foundry is amongst the best of the broad range of the Scottish firms. The technical execution of the casting directly correlates to the skills of the designer and pattern maker and in this example the quality of the carving and construction is very high.

Grand Fountain, Paisley

The recently restored Grand Fountain in Paisley, gives some idea of the powerful designs coming out of the Sun foundry at the height of its powers

2.3 Historic value

The Sun Foundry competed with the other four large architectural iron founders in Glasgow and contributed to Scotland being the most important producers of architectural ironwork in the world for around 100 years. George Smith patented a wide range of cast iron grave monuments – some with stone enclosures, others in cast iron. These were sold prolifically and are fairly common in Scottish graveyards in particular in different configurations. David Livingston purchased a Sun Foundry cast iron marker for his wife in Africa.

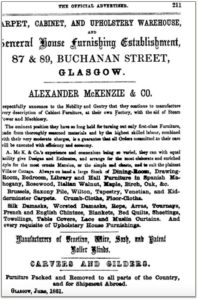

Alexander Mackenzie has only recently been revealed as a founding partner of the Sun Foundry – the

primary financier – and this increases the importance of this work. Alexander Mackenzie was a cabinet maker and upholsterer as Alexander Mackenzie and Company at 87 and 89 Buchanan Street and 165

North Street. At the time of his death himself and his son Alexander Mackenzie Jnr were sole partners.

(Edinburgh Gazette, 1875)

2.4 Scientific value

The use of cast iron in grave markers was new and actively promoted by Sun Foundry. Cast Iron was seen as a wonder material, able to bring ornamentation to the masses. Whilst failures are common through stress fractures arising from the corrosion of wrought iron fixings, the application of the medium in this way remains of technical interest, and particularly Scottish. Other firms who did produce grave markers in cast iron, such as the Etna Foundry, generally only made simple markers. Smith erected a cast iron memorial to his own family in Larbert.

2.5 Social value

The Necropolis is increasingly recognised as an important architectural and historical asset for Glasgow and Scotland. The level of visitation to the site has markedly increased over the past decade by locals and wider visitors. Conservation and restoration projects alongside research and walking tours have significantly enhanced the social value of this site. The identification of Alexander Smith as a founding partner of the Sun Foundry and the monument itself ties it to the Grand Fountain in Paisley and the Clock Tower at Bridgeton Cross; all works by the Sun Foundry.

3.0 Alexander Mackenzie

Alex Mackenzie & Company were described as suppliers of art furniture and flooring, upholsterers and cabinet makers.

From the early 1850s to the 1890s, it was based at 87–9 Buchanan Street, with a ‘steam power factory’ at 165 North Street from the early 1850s to the 1890s. The firm was originally McKenzie [rather than MacKenzie] & Crawford, house furnishers, upholsterers and paper-hangers, but from c.1852, MacKenzie continued on his own account. In an 1872 advertisement, he informed ‘architects, builders and private gentlemen’ that he had machinery for constructing inlaid floors, solidly and with close-fitting joints, and could supply ‘designs, estimates and samples’. Two years later; ‘Mackenzie’s … wood mosaic flooring, made any thickness’ was advertised, and by the 1880s, the firm billed itself as ‘Manufacturers of art furniture … venetian blinds, carvers, gilders, carpet warehousemen and general house furnishers’.

At the 1888 Glasgow International Exhibition, the firm displayed ‘Spanish and Hungarian bed-room furniture [and] a very elegant sideboard’. They panelled the Mahogany and Octagonal Salons in Glasgow’s new City Chambers around the same time, and in 1889 advertised wares including Japanese screens and Venetian glass. 4 When their lease expired in 1891, they sold off an ‘Exhibition Axminster carpet woven in one piece’, and ‘Overmantels that were £24 for £12’. 5 MacKenzie’s partner, William Miller, carried on the business alone as the ‘Charing Cross Cabinet Works’ during the 1890s, advertising ‘Architectural woodwork’ and ‘artistic carving’ as his specialities.

Notes:

1: Glasgow Post Office Directories, 1850–95

2: Scotsman, 25 April 1872, p. 2.

3: Scotsman, 20 July 1874, p. 2; Glasgow Post Office Directory, 1880–1.

4: Scotsman, 3 September 1888, p. 7; Elizabeth Williamson, Anne Riches and Malcolm Higgs, Buildings of Scotland: Glasgow, London: Penguin, 1990, p. 162; Glasgow Herald, 10 October 1889, p. 12.

5: Glasgow Herald, 4 May 1891, p. 10.

6: Scotsman, 8 June 1891, p. 1.

Alexander Mackenzie Advert – Courtesy of the Mackintosh Architecture Project

The 1871-2 Glasgow Post Office Directory has both father and son living in the West End:

Mackenzie, Alexander, jun. (of Alex. Mackenzie & Co.), ho. 104 Peel terrace, Hill st., Garnethill.

Mackenzie, Alexander (of Alex. Mackenzie & Co., and of George Smith & Co.), ho. 8 Belhaven tr.

George Smith and Co Advert

4.0 George Smith and Co, The Sun Foundry

4.1. The Smith brothers trained at Carron with their father as pattern makers. George joined the fledgling foundry of Walter Macfarlane and Co of Saracen Foundry, to become the worlds most prolific Architectural iron founders around 1851 and left in 1857 to establish the Sun Foundry. The firm grew to 600 hands within ten years making a wide range of architectural castings which were shipped across the world. Originally at Port Dundas, a bespoke Foundry was built at Kennedy Street in 1870. By 1883 Smith had been sequestrated – a knock on from the City of Glasgow Bank collapse and the circumstances of the Mackenzie family changing. The firm worked on until George retired in 1886, when the name continued to be used by others for a further 12 years in Glasgow and then in Paisley. George established the short lived Sun Foundry in Alloa, residing in Bridge of Allan until his death in 1900.

4.2. Connection with Alexander Mackenzie

In 1857 George Smith established the firm, Sun Foundry, with his brothers Gibson and Alexander and Alexander MacKenzie. The three Smith brothers were to be hands-on in the business and Mackenzie was to find money ‘without interfering in the spending of it.’4 This situation was to create problems some time later when MacKenzie died and a large part of the capital of the company was effectively owed to his estate. Initially the Smith brothers put in £250 between them and MacKenzie £500 so, right from the start, there was an imbalance in the financial structure.

When MacKenzie died in 1875, his share in the business was £47,358. George Smith had £15,000 and Gibson £7,800 standing to their credit at this time but most of the business was now owned by MacKenzie’s estate. The address for the new site is often given as Parliamentary Road, which runs parallel to Kennedy Street, one block to the south. Perhaps the offices were located there at first or the address was more recognisable.

As a result of the indebtedness to MacKenzie, the two remaining partners, George and Gibson Smith granted a bond over the Sun Foundry to the trustees of Mackenzie’s estate. This situation proved satisfactory for both sides till 1878 and substantial payments were made to the trustees.

A fire broke out at the Kennedy Street Foundry in October 1877, but it was quickly extinguished by the Central Fire Brigade. Damage was estimated at £400, covered by insurance.

The relationship with MacKenzie’s trustees however changed with the collapse of the City of Glasgow Bank in October 1878 and, since the bank was not a limited company, the shareholders were collectively liable for the losses. The collapse of the bank was disastrous for Scottish business, particularly in the Glasgow area, taking over £5 million out of the economy. Calls on shareholders, depending on their ability to pay, reached at least £2,750 per £100 share. Despite helpful actions by other Scottish banks and an appeal fund, around 1,000 of the 1,272 shareholders were ruined and the fallout from the collapse lasted many years.

In his 1883 sequestration, George Smith had cited the collapse of the bank as causing the company to suffer but neither he or Gibson appear on the list of shareholders. His comment is therefore probably related to the drop-off in trade. In the light of this situation, Mackenzie’s trustees agreed to accept smaller payments for the time being. In 1880, Angus Macleod, who had been employed as a Commercial Manager, was assumed as a Director and Partner and he put £2,000 into the business.

Pressure from Mackenzie’s trustees increased in the early 1880s and George Smith decided to apply for sequestration in 1883. However, he had dissolved the partnership just before this allowing MacLeod to carry on running the business. Asked by the court why he did this, he replied that he thought MacKenzie’s trustees were about to call for sequestration of the actual firm.

During the sequestration examination, George Smith claimed that he had paid Mackenzie’s trustees over £30,000 since the latter’s death. Notwithstanding this, the court heard that the amount due to the trustees at 31 July 1878, shortly before the collapse of the Glasgow Bank, had been £32,437 and as of January 1883 it was £32,681, indicating that it had not been reduced. Smith blamed the over valuation of the firm at Mackenzie’s death and the pressure from his Trustees as the reasons for his sequestration.

Information courtesy of Dr D Mitchell “The development of the architectural Ironfounding industry in Scotland”

5.0 Condition

The monument is in very poor condition and, as can be seen, elements have already fallen off. This is due to fastening failure, and as this process progresses, additional stress is applied to the remaining elements. Collapsing elements are of course, at risk from impact damage when they fall and as they are in most cases of “manageable” size, at risk of theft.

As can be seen in this image, the central core sits on the corner of each column pedestal. This arrangement is not ideal as the pedestals will inevitably “spread” due to the load, initiating complete failure of the structure. This anomaly can be remedied during conservation.

It is anticipated that further collapse is inevitable in the short term and complete collapse in the medium term.

Alexander Mackenzie Monument

James S Mitchell ACR FIESiS

13/02/2018