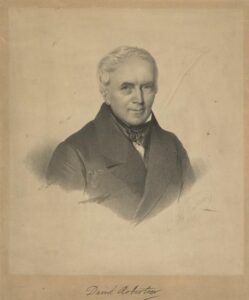

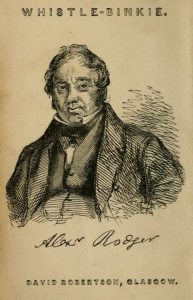

This notice of Alexander Rodger is taken from “The Glasgow Poets: their lives and poems” edited by George Eyre-Todd and published by William Hodge & Co. in 1903. (https://archive.org/stream/glasgowpoetsthei00eyreuoft/glasgowpoetsthei00eyreuoft_djvu.txt) Eyre-Todd’s text, in turn, is based on the biography of Rodger which appears in “Whistle-Binkie; a collection of songs for the social circle” published by David Robertson in 1853. (https://archive.org/details/whistlebinkiecol00carr)

Alexander Rodger

WHEN the first series of “Whistle-binkie ” was issued in 1832 from David Robertson’s shop at the foot of Glassford Street, then the favourite literary howf of Glasgow, its best and most characteristic contributions were from the pens of William Motherwell and Alexander Rodger. It was the pawky humour of pieces like Rodger’s ” Robin Tamson’s Smiddy” and “Behave yoursel’ before folk,” contrasting with the pathos of poems like Motherwell’s “Jeanie Morrison” and “My heid is like to rend, Willie,” which struck the public taste so strongly, and made the curious poetic venture a success. Not less striking was the contrast between the characters, opinions, and careers of the two contributors.

The “Radical Poet,” as Rodger has been called, was born at East Calder, Midlothian, 16th July, 1784. His mother was in weak health, and for the first seven years of his life he was cared for by two maiden sisters named Lonie. His father, meanwhile, having given up the farm of Haggs, near Dalmahoy, of which he had been tenant, had become an innkeeper in Mid- Calder, and there the future poet was put to school. Five years later the family removed to Edinburgh, and the boy was set to learn the trade of silversmith with a Mr. Mathie. This apprenticeship, however, was cut short in twelve months by the financial collapse of his father, who fled to Hamburgh. The lad was then brought to Glasgow by his mother’s friends, who had become strongly attached to him, and who apprenticed him to a weaver named Dunn, at the Drygate Toll, near the Cathedral. In 1803, seized with the prevailing fever of patriotism, he joined the Glasgow Highland Volunteers, in which regiment, and its successor, the Glasgow Highland Locals, he remained for nine years. Meanwhile, in 1806, being twenty-two years of age, he married Agnes Turner, and removed to what was then the village of Bridgeton, to the east of the city. There, to support a quickly -growing family, he added the profits of music-teaching to those of weaving, and in his leisure hours solaced himself with

the making of poetry. Perhaps his earliest effort was a poem, “Bolivar,” written on seeing in the Glasgow Chronicle, in 1816, that that patriot had set free seventy thousand slaves in Venezuela. The peculiarities, also, of the Highland members of his volunteer regiment furnished him with subjects for several satirical pieces.

This furor scribendi however, was presently to bring him to trouble. 1816-1820 were the Radical years, when, amid the distress following Waterloo, political agitation rose to a dangerous pitch. In 1819 The Spirit of the Union, a strongly political paper, was started in Glasgow by Gilbert Macleod, and Rodger became sub-editor. But after the publication of the tenth number Macleod was arrested, tried, and sentenced to transportation for life, and Rodger became a suspect. In after days he used to tell how, when his house was searched for seditious publications, he placed his Family Bible in the officer’s hands, that being, as he said, the only treasonable book in his possession, and he pointed to the chapter on kings in the second book of Samuel. Nevertheless, on the appearance of the famous “treasonable address” on the walls of Glasgow, signed by a “Provisional Government,” Rodger was actually arrested, and imprisoned for eleven days in Bridewell. There, in solitary confinement, he consoled himself, and aggravated his gaolers, by singing his own political compositions at the loudest of his lungs.

In 1821 he obtained employment as inspector of cloths at Barrowfield Printworks, and during his eleven years in that situation he composed most of his best pieces. At the same time the poet’s political sympathies were by no means hid under a bushel. When George IV. , in 1822, visited Edinburgh, an anonymous squib from Rodger’s pen, “Sawney, now the King’s Come,” appeared in the London Examiner, creating much speculation in the mind of the public, and no little annoyance to Sir Walter Scott, whose loyal “Carle, now the King’s Come,” had appeared simultaneously. And when Harvie of West Thorn blocked up the footpath through his property by Clydeside with a wall, it was by Rodger’s strenuous energy that the public movement was directed which vindicated the right of way.

A friend started a pawnbroking business in Glasgow in 1832, and induced the poet (of all men) to become its manager. In a few months, as might have been expected, he threw up the position, and in a rhymed epistle to the managers of Barrowfield works declared his readiness to do anything “fire their furnaces, or weigh their coals, wheel barrows, riddle ashes, mend up holes,” rather than stay where he was

“Obliged each day and hour to undergo

The pain of hearing tales of want or woe.”

He found a place shortly, however, as reader and reporter on the Glasgow Chronicle; and a year later, on John Tait starting a Radical weekly, the Liberator, Rodger became his assistant. Tait died, and the paper came to grief, but in a few months the poet found a place in the office of the Reformer’s Gazette, which he kept till his death. In 1836 some two hundred of his fellow-citizens entertained him to dinner and presented him with a silver box full of sovereigns “a fruit not often found on the barren slopes of Parnassus.” He died 26th September, 1846, and was buried near William Motherwell in Glasgow Necropolis, where a monument marks his resting-place [Compartment Mnema]. On hearing of his death the Scotsmen in Cincinnati collected and sent to David Robertson, the publisher, a sum of £12 as a gift to the poet’s widow and children.

Rodger’s first avowed appearance as an author was in 1827, with a volume, “Peter Cornclips, a Tale of Real Life, and Other Poems and Songs.” In 1838 he published another volume of “Poems and Songs, Humorous and Satirical “; and in 1842 “Stray Leaves from the Portfolios of Alisander the Seer, Andrew Whaup, and Humphrey Henkeckle” these being the nommes de plume above which the satirical contents had appeared in periodicals. Since then select editions of his poems have been edited by Mr. Robert Ford in 1896 and 1902. But the poet’s name is chiefly associated with “Whistle-binkie,” in which his best pieces appeared, and of which, after the death of Carrick in 1835, he became editor.

The political heat of that time has passed away, and in consequence “Sandy ” Rodger’s satires have lost both point and sting, but his songs, touching slily and not unkindly the foibles of ordinary human nature, remain amusing as ever, and the hot-headed, tender-hearted, Radical poet is not likely to be forgotten. The late Crimean Simpson has recorded of him: “I was familiar with his round, short figure when he was connected with the Reformer’s Gazette, Peter Mackenzie’s paper. I used to see him regularly about Argyle Street, and I have often heard him sing his own songs at the Saturday Evening Concerts, which he did in a genial, pawky way.”

Alexander Rodger Monument

In the Glasgow Herald of Friday July 28 1848 is the following report:

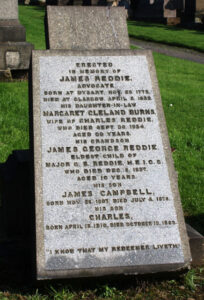

MONUMENT TO THE MEMORY OF THE LATE MR. ALEXANDER RODGER.

A few gentlemen, who have interested themselves in the erection of a monument over the resting place of the late Mr. Alexander Rodger, along with two of the deceased poet’s sons, assembled, on Monday afternoon in the Necropolis, for the purpose of seeing the ceremony performed of laying the foundation-stone. The monument, which is nearly completed, is of the Grecian order, and is surmounted by a sarcophagus, upon which is carved a very correct medallion portrait of Rodger. Mr. James M’Nab of the Glasgow Constitutional Office, previous to laying the stone deposited a bottle, hermetically sealed, in a cavity in the basement, containing a volume of the poet’s works, the manuscript of his latest production, copies of the Glasgow newspapers, the card of Mr. Mossman, the artist, and several other documents. The inscription upon the monument, which, it may be mentioned, overlooks Drygate Bridge, the scene of one of the poet’s earliest and most humourous songs, is as follows :—

“To the Memory of

Alexander Rodger,

A poet

Gifted with feeling, humour, and fancy;

A Man

Animated by generous,

Cordial, and comprehensive sympathies,

Which adversity could not repress,

Nor popularity enfeeble;

This Monument

Is erected in testimony of public esteem.

Born

At Mid-Calder, 16th July, 1784;

Died

At Glasgow, 26th September, 1846.

“What though with Burns thou couldst not vie,

In diving deep, or soaring high.

What though thy genius did not blaze

Like his to draw the public gaze;

Yet thy sweet numbers, free from art,

Like his can touch—can melt the heart.”

The inscription was penned by Mr. Kennedy, author of “Fitful Fancies,” and the concluding lines of poetry are from an Ode to Tannahill, by Rodger. The design of the monument is exceedingly chaste, and the execution of the likeness does much credit to Mr. Mossman— Guardian.