The source of this profile is Stewart Noble, a Blue Badge Guide and author from Helensburgh.

He was principle editor of “200 Years of Helensburgh” which obtains a lot of information on the Kidston family. The principal section on the Kidston is in a chapter entitled “The Benefactors” and was written by Helensburgh Heritage Trust’s treasurer and company secretary John Johnston, whose wife Penny is a Kidston. There are also other numerous references to the Kidstons throughout the book.

This is an excerpt from the book with the additional of names and dates of two of the wives who are also buried in the Glasgow Necropolis.

This is an excerpt from the book with the additional of names and dates of two of the wives who are also buried in the Glasgow Necropolis.

The Kidstons

The Kidston family have lived in and been involved with Helensburgh since the 1830s. In one of the obituaries in the local paper it was said: “the name of Kidston is writ large in all the recreative and philanthropic institutions of our beautiful town.”

The background of the family is of some interest as it explains the source of their business interests and fortunes in the first half of the 19th century and is a fascinating illustration of the entrepreneurial developments of the West of Scotland at that time.

There had been Kidstons living at Logie, close to Stirling, since the middle of the 16th century and for generations they had been farmers – not always successful. In 1765 a Richard Kidston, born in 1736, emigrated to Virginia and later the same year his wife and family joined him. In 1773 Britain attempted to start taxing her American colonies, which then joined together to form the United States of America. Richard joined the United Loyalists being a Royalist like his forebears in Scotland. In 1776, when the American War of Independence started, he fled to Maine. It would appear that he with many other United Loyalists fought with the British Army and he was captured by the colonists at New York on 25th November, 1783. Managing to escape from the prison in New York he fled in a small boat with only what he was wearing. He was lucky to be picked up in the Atlantic by a ship proceeding to Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Richard Kidston established himself as a merchant at Halifax and eventually as a shipowner. He exported timber to Glasgow and imported goods from that city. He died in 1819 at the age of 79. His many ships passed to his son, William Kidston, who had by this time moved to Glasgow and formed his own business, William Kidston and Sons, with offices and warehouses in Queen Street.

William Kidston had been born in 1757 at Logie and in 1784 married Catherine Glen at Halifax and they had a family of seven; he died in 1831. Business prospered and by 1820 the firm was involved in wholesale china manufacturing, shipping (they acted for Cunard, another Halifax family) and general merchanting. The potteries in Glasgow at Anderston and Finnieston, Verrivale and Lancefield were extensive with a large export trade to South America and the East Indies – the Scottish Pottery Society has identified several pieces found in Indonesia.

William Kidston had been born in 1757 at Logie and in 1784 married Catherine Glen at Halifax and they had a family of seven; he died in 1831. Business prospered and by 1820 the firm was involved in wholesale china manufacturing, shipping (they acted for Cunard, another Halifax family) and general merchanting. The potteries in Glasgow at Anderston and Finnieston, Verrivale and Lancefield were extensive with a large export trade to South America and the East Indies – the Scottish Pottery Society has identified several pieces found in Indonesia.

By 1839 the firm had become too large with too many Kidstons trying to run it and it was decided to divide the business as follows:

1. Richard Kidston – the home market (William Kidston and Sons);

2. Archibald Glen Kidston – the export and shipping fleet (AG Kidston and Co). This business prospered under his son, George Jardine Kidston (1835-1909) who lived at Finlaystone near Langbank in Renfrewshire. His granddaughter married General Sir Gordon Macmillan whose descendants live there today. The shipping business prospered and developed into the Clyde Shipping Company;

3. Robert Alexander Kidston – the potteries (Kidston and Co). There are a number of articles on the history of the potteries in the journals of the Scottish Pottery Society. Although or possibly because the products were of a high quality the firms were not financially successful and eventually Robert Kidston moved to Stirling. His son Adrian worked for the family firm, William Kidston and Sons, and then went into banking, becoming manager of the Helensburgh branch of the Clydesdale Bank in 1885.

Buried in the Necropolis

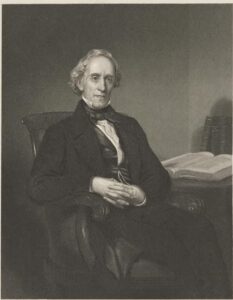

Richard Kidston (1784-1865). It is said that Bailie Richard Kidston came to Helensburgh in 1845 but he was Provost of the town in 1836! He had been Bailie in Glasgow from 1835-1845 and a partner in William Kidston and Sons. He was also involved in the early days of the Clydesdale Bank and became a director of the Bank in 1843 and chairman in 1851 and 1862. Until 1856 a director had to live within 10 miles of Glasgow, the coming of the railways rendering this qualification unnecessary. Perhaps Richard Kidston had more than one house as he lived, together with his two unmarried sons William and Richard and a daughter Catherine at Seabank, a villa said to have been built about 1820 in classic palladian style, on the river side of East Clyde Street, opposite the foot of Grant Street. He was Provost of Helensburgh in 1836 and again from 1840-49.

His latter years as Provost were taken up with the vexed question of a new pier. An Act of Parliament had been obtained in 1846 authorising the local authority to erect a pier and levy rates on it. But an unfortunate agreement had been made with the promoters of the Caledonian and Dumbartonshire (sic) Railway by which they, in consideration of certain privileges to be granted, undertook to advance money to build a pier. The line was not at that time completed; but an ill-advised litigation was raised by the council against the company to compel the implementation of the bargain which after years of delay was decided against the council. Various attempts at arrangement and compromise were made by Mr Kidston and a minority of the council, and would have been successful but for the litigious inclinations of his colleagues who wrangled constantly over every subject. The action ended with the House of Lords and the town council obtained nothing more than a large place in the Law Reports. Fame is dearly bought.

The foundation stone of the West United Free Church (now known as the West Kirk) was laid in 1853 and the cost of £4,500 was to a very considerable extent contributed by Mr Richard Kidston.

The East End Park for the town was walled and laid out by him and the gift of the land by Sir James Colquhoun secured through him. He liberally aided the building of Park Free Church and Manse and he fostered many religious and philanthropic schemes. He died in 1865.

His Wife – isabella Mirrlees (1783 -1843)

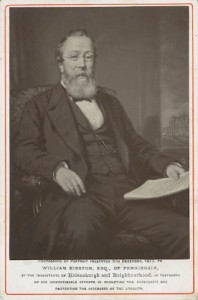

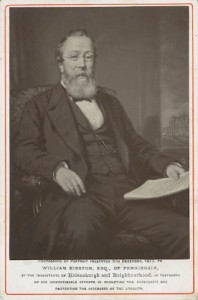

William Kidston (1813-1889). On his father’s death William Kidston continued to live with his brother and sister but in 1869 moved to the newly built mansion of Ferniegair, West Clyde Street, in what was then the Parish of Row [today Rhu]. Similar in scale to Cairndhu, its next-door neighbour, Ferniegair (architect, John Honeyman) had very large grounds stretching back to West Argyle Street, which over the years were whittled away. In the 1960s the house was demolished and A Trail and Son built a modern housing estate on the site, but one of the roads was named after the house. The coachman’s lodge was retained, enlarged and modernised and sold as a private home – it stands today at 196-198 West Princes Street.

William Kidston was closely involved with the Free Church Sunday School and in the early days of the Free Church came to the front as a leader of the Highland Host. In this context he was known all over Scotland. He supported Park Church and as the senior Elder was involved in the dispute in 1874 when there was an attempt to change the long-established custom of “standing during prayer and sitting during the exercise of prayer”.

In 1874 he became involved with saving as an open space the piece of land then known as Neddy’s Point and now as Kidston Park. It has been written that a “well-known local artist of worldwide fame” had decided he wished to acquire the point and build himself a villa. On the point was a cottage occupied by the Duke of Argyll’s fisherman, by the name of Neddy – hence the name. William Kidston organised a subscription, supported by himself, Sir James Colquhoun and Provost Breingan to acquire the land from the Duke of Argyll and lay it out as a park. The cost was £552 (£320 per acre, or £790 per hectare) and included the rights to the foreshore and the mussel beds, but the Duke retained the right to land from and embark to the Castle of Rosneath. A local writer, though full of praise for the new park, thought it rather small. William Kidston offered a subscription of a further £500 to add to the land but nothing further was done. How it now comes to be known as Kidston Park is not clear as there is correspondence showing that Sir James Colquhoun wrote that, in his view, the park should not bear the name of any of the contributors, but an inscription still in existence states that the park was chiefly the gift of William Kidston and that he left funds for maintenance. Since then road-widening, a car-park and the building of houses on the land not acquired have reduced the attraction of the park but there are photographs showing the bandstand and there was a jetty at the water’s edge.

In 1877 Mr Kidston was honoured by a dinner in the Queen’s Hotel for his spirited action in the Helensburgh Railway Station dispute. There were diverse opinions on his and others’ efforts which prevented the Railway Company from forming their “Station in the sea” at Helensburgh Pier, and thereby laid them under the necessity of making the Station and Pier at Craigendoran. But there were hundreds who agreed it would have been ruinous, reducing Helensburgh from being a flourishing and favourite watering place into “a dirty coaling place”. The Bill before Parliament by the North British Railway Company was opposed by what was known as the Kidston Bill and the House of Commons declared that their “preamble had not been proved”. William Kidston was presented with a portrait painted by Sir Daniel McNee.

In 1863 a number of magistrates and other gentlemen connected with the West of Scotland interested in the cause of Sabbath Observance and Sobriety, in testimony of their appreciation of his zealous and efficient services involving the Scottish licensing system and the Public Houses Acts, presented to William Kidston a solid silver table piece three feet high in the form of three nubile girls holding aloft the dishes for fruit. This can be seen in a formal New Year photograph of an assemblage at Ferniegair about 1900.

There were never any doubts about the political party that their cousin and future prime minister, Bonar Law, would join if he entered politics. [Bonar Law had been born in Canada and his mother was Eliza Ann Kidston, but she died when he was two years old; 10 years later he was brought to Scotland for his upbringing and education by his Kidston relatives.] The Kidstons, unlike the great majority of the Scottish middle class to which they belonged, were ardent Conservatives. There is a tradition that Disraeli once visited Ferniegair. Middle-class Scotland was in general at that time a stronghold of Liberalism.

William Kidston had sponsored his cousin Andrew Bonar Law into the family firm of William Kidston and Sons. When in 1885 William and his brothers wished to wind up the affairs of the firm and retire, the Clydesdale Bank offered lucrative merger terms. However they realised that such a deal would have left Bonar Law in a difficult situation. His recent biographer describes how Bonar Law found a position in William Jacks, a metal trading company in Glasgow, and how William Kidston and his brothers advanced him the money to buy a partnership in that firm. Incidentally William Jacks was a Helensburgh neighbour.

Richard Kidston (1816-1894) was a partner in the family firm who inherited Ferniegair on William’s death and who died unmarried. Like his siblings he was involved with the Church and in 1860 a new manse for the West Parish Church was acquired and new bedrooms added principally through his generosity. In 1893 he gave £1,000 to the Victoria Infirmary [Helensburgh] as shown on its Donor Board.

Charles Kidston (1820-1894), a brother of William lived at Glenoran, Glenoran Road, Rhu, another large house now demolished. He was married but had no children and was a director of the family firm. Both he and his wife left substantial fortunes which together with a house went to Bonar Law’s family. Donations by Charles and his wife to the Victoria Infirmary [Helensburgh] are shown on the Donor Boards in the entrance to the Infirmary – £525 in 1895 and £1,000 in 1898. The year after his death his trustees donated £2,600 to the Commissioners of Helensburgh Pier, thus enabling the abolition of pier dues (ie charges to passengers). This was the cause of much festivity within the town.

His Wife – Janet Gray (1833 – 1896)

Catherine Kidston (1824-1906) spent nearly all her adult life in Helensburgh moving at the age of 18, following the sudden death of her mother, with her father Richard and brothers to Seabank and later to Ferniegair.

Her father was closely involved with the St Enoch Free Church in Glasgow and after the Disruption the family continued to be closely involved with the Free Church as well as her work with Sunday Schools and as a District Visitor. In addition she was a partner in the family business, unusual for a lady in those days. Her obituary refers to band performances at Kidston Park by the boys from the “Empress” [a training ship moored in Rhu Bay] being due to her thoughtful kindness (presumably financial). The boys disembarked at the jetty at Kidston Park and marched through the town to their appointments. It continued that she was esteemed for her religious, temperance and philanthropic work and many acts of unostentatious beneficence and it was said her motto was “to live as we would wish to have done when we come to die”.

Shortly after the death of the Reverend Alexander Anderson in 1891, who had retired from the West Kirk in 1882, she gifted the [West Kirk’s] spectacular porch, designed by William Leiper. This much-crocketed extension is alive with fantastic birds and beasts munching their way around the stepped cornice. When he retired he had been presented with a silver fruit set which consisted of a central raised basket, embossed with a view of the Church, and four silver dishes. This set was apparently left to Catherine by the Reverend Anderson.

Adrian MMG Kidston (1848-1912), son of the pottery director Robert Alexander Kidston, became a banker and came from being agent at Crieff to Helensburgh in 1885 as manager of the Clydesdale Bank in James Street and lived in a house attached to and over the bank until he moved to Ferniegair. He served on the parish council for 18 years, becoming a town councillor in 1902 and Provost in 1911, dying in office in October 1912, a month after he had welcomed the dignitaries who came to the celebration of the “Comet” centenary [Henry Bell’s steamship]. His obituary refers to his involvement with the Girls’ School Company (of which St Brides was part] and also with Larchfield School. It also says that the town council owes in a large measure the building and equipping of the Victoria Infirmary [Helensburgh] to his wonderful gift of raising money. Like other members of the family he was a keen sportsman being captain of the Golf Club 1901-05 and president of the Curling Club and vice-president of the Royal Caledonian Curling Club in 1907-08. There is also mention of cricket, tennis, quoits, bowling, swimming and rowing. He was also president of the West of Scotland Rosarian Society and the Helensburgh and Gareloch Horticultural Society.

In the late 19th century the property on the west side of James Street between Princes and King Streets was somewhat notorious. Originally the “Barracks” had been built as dwellings for railway or construction workers and had become a very poor class of house. They were in the area covered by Miss Catherine Kidston as District Visitor for the Sunday School. Her obituary said that she had handed it to the town but the deed of gift was signed in 1907, after her death, by Adrian Kidston with the condition, accepted by the Provost, magistrates and councillors that it be preserved and used at all time coming hereafter “as a place of recreation for the inhabitants of Helensburgh” but he carefully added that “being used otherwise would revert to him or his heirs”. It now serves as a children’s playground.

In 1988 a plan was put forward by private developers to build a medical centre together with flats on the site and a small play area under cover on an adjacent site – the plan also involved converting the adjoining but disused St Bride’s Church into a new library. Admittedly the playground had been allowed to run down and there was a need for a new medical centre but a number of local residents and others were unhappy at the loss of the open space of which there was little in or near the centre of the town. Descendants of the donor raised objections to the proposals on the grounds of the loss to the community and after lengthy legal correspondence and a site meeting the plan to use the playground was dropped. In due course a new and larger site was found for the doctors and a new library was built on the site of the demolished Church.

In 1999 the playground was refurbished, with splendid new railings, with financial help from local businesses and also by members of the Kidston family.

RAPR (Dick) Kidston (1894-1972) inherited Ferniegair from his father, Adrian Kidston. Educated at Larchfield, Fettes and Cambridge University he served throughout World War I in the Royal Field Artillery in Egypt and Palestine where he was mentioned in General Allenby’s despatches. In 1922 he married Penelope Paul the daughter of Henry Paul, a director of Matthew Paul and Company, engineers in Dumbarton, who in 1897 had built The White House in Upper Colquhoun Street. The architect there was Baillie Scott who was awarded the second prize in the competition to design A House for an Art Lover. This competition made the reputation of Charles Rennie Mackintosh even though he failed to complete his entry – no first prize was awarded. Regrettably after the house was sold in the 1920s some of the major features were changed.

Also in the 1920s Ferniegair was sold and Mr and Mrs Kidston moved to Edinburgh returning to Helensburgh in 1939. Dick Kidston served throughout World War II in which his only son Adrian, a Lieutenant in the Royal Artillery, was killed in action. Adrian was in the 52nd Lowland Division which was designated as a Mountain Division – there is no other such unit in the British Army. They added “Mountain” to their Divisional shoulder flash but in the end went into action below sea level where he was killed in the amphibious landing at Walcheren, Holland. After the war Dick Kidston was a town and county councillor in the 1950s and 60s.

W H Kidston (1852-1929), nephew of George Jardine Kidston, lived at Rosebank, 150 West Princes Street. He was chairman of AG Kidston & Co Ltd whose business in the 20th century was iron and steel merchants but he concentrated on the insurance broking side of the business and became a senior executive and later a director of the Royal Insurance Company. He was a keen sportsman playing rugby for Scotland against England in February 1874. He was also an enthusiastic bowler, being club president in 1921; as a devotee of golf, he was one of the original founders of the Helensburgh Club – captain in 1894-96 and president in 1927-28; he was also a member of Helensburgh Curling Club. His obituary in the local paper said that for a long number of years he was closely identified with the public life of the Burgh and in many ways contributed to the advancement of the town and the welfare of its people. It was said his philanthropy was well directed in particular to the Town Mission and practical interest in the religious teaching of the young. The Plotholders Association had, in him, a sympathetic friend and it was typical that he should grant the use of a large field in front of his house for the culture of vegetables. It was his custom to visit the field and watch the progress being made on the various plots. There are now houses on this field. His son William, who was unmarried, a captain in the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, died of wounds suffered at Ypres in 1917 and is buried in the Commonwealth War Cemetery at Etaples.

A printed letter to the congregation of the West Kirk dated 11th December, 1914 details sixty members of the congregation who were serving King and Country – numbers 20 to 23 were members of the Kidston family – Dick Kidston, William Kidston, James Kidston Law and Charles Law – the last three were all killed.

Annabel Kidston (1896-1981) was another member of the family who lived in Helensburgh, a wood engraver, etcher and painter who studied at the Glasgow School of Art, under Greiffenhagen and Forrester Wilson and at the Slade School of Fine Art under Henry Tonks and Wilson Steer. She moved to St Andrews and became the first president of the Art Committee of that town.

The present members of the family living in Helensburgh are: Mrs Marion Watson, a granddaughter of Dr Robert Kidston FRS, and a cousin of William Kidston, a noted palaeobotanist who lived in Stirling. Mrs Watson has lived all her life in the town and has been and is on many local committees and synods [and for these services she was awarded an MBE in 2007]; and Mrs Penny Johnston daughter of Dick Kidston.

The Helensburgh Heritage Trust website also contains a photo of a mass Kidston party.