Hugh Galbraith MM

Saturday, June 28th, 2014Joseph F Gomoszynski

Sunday, November 13th, 2011Profile supplied by and copyright of Morag T. Fyfe

A Polish translation can be downloaded here

Joseph F Gomoszynski c1813-1845

Standing near the summit of Glasgow Necropolis [in Compartment Sigma, lair 52] is a relatively modest stone which catches many visitors’ attention. It commemorates Joseph F. Gomoszynski Lieutenant in the late Polish Army who fought for the Independence of his country in 1830 and died in exile at Greenock on 27th October 1845, Aged 32

There has been a certain amount of speculation on internet websites as to who Joseph Gomoszynski is but no one seems to know anything about him. Using various sources it has now been possible to find out a little about him and his family in Britain.

Judging by his age at death Joseph was born c1813, probably somewhere in Poland. On the title page of a book he published in 1843 he describes himself as a lieutenant in 1st Regiment of Polish Lancers. At the beginning of the book he says that he fought in the November Uprising of 1830/31 against the Russians, was imprisoned by the Prussians, left his native country in 1832 and eventually arrived in England in 1836.

His arrival in England in 1836 is recorded on a passenger list listing Aliens arrivals. He came to London on 12th July 1836 from Danzig on the ship Lachs and is described as being from Poland but as travelling on a Russian passport. It was specifically noted that this was the first time he had come to England.

Nothing further is known about Joseph until his marriage to Jane Hughes of Liverpool is announced in the Greenock Advertiser. The couple married on 30th December 1839 at St John’s Episcopal Church, Greenock.

The couple did not remain long in Greenock as their first daughter, Catherine Stanislove, was born late in 1840 in Leeds, probably in Headingley where Joseph, Jane and Catherine are found living, at North Lane Headingley, next year when the census was taken. The census entry confirms that Joseph was of foreign birth and tells us that Jane, though English, had not been born in Yorkshire. The only other piece of information is that Joseph gives his occupation as Professor (no less!) of Languages.

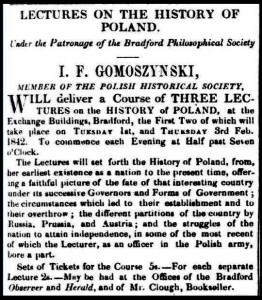

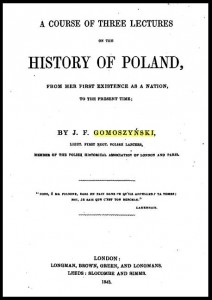

Around December 1841/January 1842 a series of adverts in the Liverpool Mercury and the Bradford Observer show that Joseph gave a series of three public lectures on the History of Poland. These lectures were later published, in 1843, as A Course of Three Lectures on the History of Poland: From Her First Existence as a Nation, to the Present Time and priced at 3s 6d.

Another daughter, Emily Jane, was born in Leeds in 1842 but by 1845 the family was back in Greenock at 4 Boyd Street. However they may not have come directly from Leeds to Greenock as an entry in Hutcheson’s Greenock Register and Directory for 1845-46 suggests. Under French and German Languages and Literature, an entry for Lieutenant J. Gomoszynski, describes him as “late Master of the Modern Language Department, Stanwix Academy, Carlisle”. It is not known when or for how long Joseph taught at Stanwix Academy but as he feels it worth mentioning in this directory entry in 1845 it seems likely he had been there immediately before arriving at Greenock.

Two further children were born to Joseph and Jane in Greenock: Joseph Francis Dudley about August 1845 and the mysterious Casimir Thomas who, from later evidence, may have been a twin of Joseph junior, or a younger (posthumous?) brother born 1845-1846.

The family did not remain complete for long as Joseph senior died at his home, 4 Boyd Street, Greenock of a heart aneurism on the 27th October 1845 at the early age of 32 years and was buried in the Necropolis, Glasgow on 1st November. Nine months later on 15th July 1846 his infant son Joseph junior died of whooping cough at the same address in Greenock and was buried beside his father in the Necropolis on 18th July.

Those are the only facts that have been gleaned so far about the life of Joseph Gomoszynski and they are not sufficient to put much flesh on his bones without indulging in a certain amount of speculation.

No records have so far been found for him in Poland and one has to rely on what he, himself, says about his early history. Joseph was probably born in that part of partitioned Poland under Russian rule known as Congress Poland. He can only have been about 17 when the November Uprising (29th November 1830 – 21st October 1831) started in Warsaw. The revolt was led by young Polish officers and cadets from the military academy in Warsaw and Joseph’s age and the fact that he describes himself as a lieutenant in the 1st Regiment of Polish Lancers would certainly fit the scenario that he was a cadet at the academy. After bitter battles against the numerically superior Russians the last 20,000 men of the Polish army crossed into Prussian Poland on 5th October 1831 and laid down their arms there rather than surrender to the Russian authorities. The Prussian authorities interned the men and expelled them from Prussian Poland in groups of 50-100. This could fit with Joseph’s description of being imprisoned in the Fortress of Weichselmunde near Danzig (now Wisłoujście near Gdansk) before being forced to leave Poland in 1832.

Map of Poland showing that part of the country (Congress Poland) under Russian control where the November Uprising took place

Joseph seems to have supported himself by teaching languages. It is likely that when he arrived in England he could already speak several languages though not necessarily English at that time. There is evidence that he taught in Leeds, Carlisle and Greenock though he does not seem to have stayed long in any of these places. At Carlisle he taught at Stanwix Academy, probably a private school in the village of Stanwix just north of Carlisle. In Greenock he seems to have set up his own academy at 5 Boyd Street next door to his home at number 4. It is likely this was also a private school and one wonders whether there were any other teachers concerned with it, or whether Joseph was the only one. (8)

It was mentioned above that Joseph published a slim (96 pages) book in 1843 under the title A Course of Three Lectures on the History of Poland: From Her First Existence as a Nation, to the Present Time. At the front of this book are two pages listing 91 persons who subscribed for one or more copies of his book. Presumably some of them had attended his lectures of December 1841 or February 1842 and it is interesting to speculate how many of them he might have known personally. The subscribers fall into three distinct groups: 58 from Leeds, Bradford and Otley (for 66 copies), 20 from Greenock (for 38 copies) and 5 from Liverpool (for 27 copies), plus a scattering of singletons. The 58 subscribers from Yorkshire can be accounted for by the fact that Joseph was living in Leeds when he gave the lectures and the 20 from Greenock may reflect the fact that he was living in Greenock by the time the book was published. It is also notable that it is to a Greenock man, John Denniston, that the book is dedicated (and John Denniston subscribes for 10 of the Greenock copies).

Four of the subscribers need more attention. Colonel K Lach Szyrma in Devonport subscribed for 1 copy. Lach Szyrma (1790 – 1866) was a Polish philosopher, writer and journalist, translator and political activist. He was a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Warsaw when the November Uprising broke out and was appointed colonel of a regiment. Like a number of his compatriots he came to Britain after the Uprising finally settling in Devonport. The other Pole on the list is Lieutenant Constantine Ordon of Greenock. This may be Julian Konstanty Ordon (1810 – 1887) who commanded one of the redoubts defending Warsaw from the Russians. Julian Ordon was of a similar age to Joseph and it seems very likely they knew one another. The third subscriber is Lord Dudley C. Stuart who was an influential member of the Literary Association of the Friends of Poland co-founded in 1832 by Thomas Campbell, the poet. It may be significant that one of Joseph’s sons is named Joseph Francis Dudley. The fourth subscriber is Mrs. Hughes of Liverpool who put her name down for 18 copies. Bearing in mind that Joseph married a Jane Hughes of Liverpool there seems no doubt this is his mother-in-law doing her bit to support him; there are also 3 Miss Hughes listed in Liverpool and Greenock and a Mr. James Hughes in Monte Video who between them subscribed for another 10 copies, surely more family members.

Lastly one has to try to answer the question: why was this Polish refugee buried in the Necropolis and a stone put up to commemorate him? Why was Joseph not buried at Greenock? A burial lair in a good position in the Necropolis was not cheap in 1845 and neither was a stone monument. Did his widow, or her family, have enough money for the lair and stone or did someone else pay for it? It seems likely that Joseph was a member of the Literary Association of the Friends of Poland judging by the names of some of the subscribers to his book and this society had a branch in Glasgow known as the Glasgow Polish Association. He described himself as a member of the Polish Historical Association of London and Paris on the title page of his book and one could speculate whether these two bodies rallied round to make sure he had a seemly burial and commemoration.

The Gomoszynski Family

Jane Hughes or Gomoszynski born Liverpool 1812/3; died Conway, Caernarvonshire Apr-Jun 1877.

Catherine Stanislove Gomoszynski born Headingley, Leeds, Oct-Dec 1840; died Marylebone, London Oct-Dec 1919.

Emily Jane Gomoszynski born Headingley, Leeds Apr-Jun 1842; died Droitwich, Worcester Jul-Sep 1897.

Joseph Francis Dudley Gomoszynski born Greenock August 1845; died Greenock 15th July 1846.

Casimir Thomas Gomoszynski born Greenock 1845/46; died Cricklewood, Middlesex 25th March 1928.

When Joseph Gomoszynski died in 1845 he left a widow, Jane, and four children. It has been possible to find out a little about what happened to Jane and her children after Joseph’s death to try and complete the story of this family.

It has already been stated that Joseph junior died the year after his father and was buried beside him in the Necropolis. There is then a gap of about fifteen years and no trace of the family until 1861. At the census that year Jane and her two daughters are living in Marylebone, London. Interestingly Jane gives her occupation as school mistress which matches that of her husband previously, though there is no indication of what she taught. There are three boarders in the household which might suggest Jane was hard up and taking in boarders to help make ends meet. On the other hand she can afford to employ three live in servants – cook, kitchen maid, and housemaid. Ten years later Jane and her younger daughter Emily are living on their own at Llandrillo, Caernarvonshire and Jane dies there or close by in 1877.

Emily, the younger daughter, next pops up in 1891 when she is found visiting George Heslop and family in Newcastle upon Tyne upon census night. Twenty years later in 1911 it is her sister Catherine’s turn to visit the same family of Heslops now relocated to Dulwich, London. It seems that George Heslop married Sarah Anna M Lea, who turns out to be an older sister of Casimir’s wife Mary, in 1878. Furthermore the couple had a daughter in 1892 whom they named Anna Casimira

Apart from these two appearances in the census nothing more is known about Emily and Catherine until they die: Emily in 1897 at Droitwich, Worcestershire and Catherine in 1919 in the district of Marylebone, London.

This leaves the mysterious Casimir Thomas Gomoszynski. He is a mystery because the first record of him is in the 1881 census when he is already 35 years old. His unusual surname, the fact that this census records him as being born in Greenock about 1845/6 and Emily and Catherine’s later links with the Heslop family (see above) are the only pieces of circumstantial evidence to suggest he is a son of Joseph senior.

At the census in April 1881 Casimir is visiting Charles and Hannah Lee and their youngest daughter Mary Adeline Beaumont at Morpeth, Northumberland. It turns out that Casimir is engaged or about to become engaged to Mary Lee as the couple marry that October in Morpeth. Helpfully he gives his occupation in the census as a civil engineer and Burgh Surveyor at Tynemouth.

Peter Giles

Monday, July 25th, 2011Sarah Dart supplied this Profile. Peter Giles, father of James Giles, R.S.A., was her third great grandfather.

Peter Giles was born probably in Aberdeenshire, being possibly the one of that name baptised in Clatt in 1776, son of George Giles and Elspet Paxton. In 1800 he married Jean Hector (a native of Rhynie & Essie) in Old Machar, Aberdeen.

Peter was an artist and a pattern designer at the cotton mills in Woodside (now part of Aberdeen). He also later opened an art studio and taught drawing and painting. Peter and Jean had two children in Aberdeen: James, born 1801 (who became a well-known artist and member of the Royal Scottish Academy) and Isabella in 1802.

Apparently, the marriage was not a happy one and Peter left his wife and children in about 1812 and went to Glasgow, where his drawing academy appears in the directories from 1812-1820.

His daughter Mary Isabel was born in 1819 and family lore has it that her mother (also named Mary Isabel, surname unknown) died soon after her birth. Peter then took the baby to Belfast, where he taught drawing and painting for about 15 years.

In the summer of 1835, Peter decided to go back to Glasgow. Mary Isabel stayed behind and married in Belfast, she and her husband leaving for America two years later. “Peter Giles, teacher of drawing and painting” appears in the Glasgow directory again in 1839.

From the letters he wrote his younger daughter it is clear that he found it difficult to make a living in Glasgow after being away for so long, but he wrote enthusiastically about the church services at “St Marey’s Chaple” and mentioned several preachers whose speaking he had enjoyed.

In 1840 he caught the influenza and died, far from any of his family and attended only by the house factor, Robert Rattray, who wrote Peter’s son James in Aberdeen and daughter Mary Isabel in Connecticut about his last illness (his elder daughter Isabella had died in 1833).

Peter Giles was buried in the Necropolis on 15 June 1840, in Iota No 6.

The Gourlay Family

Friday, March 11th, 2011Photographs and information supplied Dr James T. Farquhar, son of James Gourlay II’s middle daughter.

Zeta Divisiton in the Glasgow Necropolis.

The graves of the Gourlay family are in the NorthWest spur. There have been five burials in it. These are as follows.

Mary Brown Hastings Gourlay (Moffat), died 1877 – Dr Robert Gourlay’s first wife

Jane Gourlay (McPhail), died 1911 – Dr Robert Gourlay’s second wife

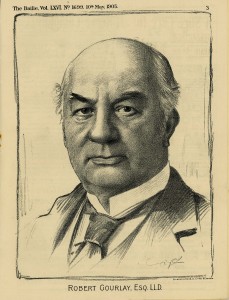

Dr Robert Gourlay, 1840-1916 – died aged 76 – only son of James I

James Gourlay II 1869-1952 died aged 83 – eldest son of Robert

James Gourlay II 1869-1952 died aged 83 – eldest son of Robert

Ella Gourlay (Moffat), died 1952 – wife of James II

The history of the Gourlays in St Andrews goes back several centuries and there are many Gourlay graves in the old St Andrews cemetery.

James Gourlay I (1804-1872) moved from St Andrews to Glasgow in 1819 along with his mother Agnes Liddel and his three brothers. Following an apprenticeship, he set up in business with his brother Robert, working as a commercial traveller and in 1838 he established the Commercial Travellers’ Society of Scotland, remaining its treasurer until his death.

In 1841 he switched to accountancy, and from 1848-1855 served on Glasgow’s City Parochial Board, where he worked on reforming rates and taxes. About 1853 he retired from business but returned in 1855 in a new capacity. At this time the Bank of Scotland had only one office, in Ingram Street. The Directors now resolved to open a branch in Laurieston, at the south end of the Jamaica Bridge, and they offered the agency to him offering that the branch should not be under Ingram Street, but should correspond direct with head-quarters. Somewhat to the surprise of his friends, he accepted the offer, and he was thereafter known as a banker.

“Banker Gourlay” is a distinct and a pleasant memory – the tight, active figure and the cheery spirit on the verge of three score and ten, the full suit of black and the high old- fashioned stock, the

frequent snug-box, the simple, kindly manner, the good sense and good humour, the loyalty to the bank, its honour and its interests. Nothing pleased the old man better than to look out from the door of his room and see the counter crowded with customers. It was a treat he could have often enough. He threw himself into his new enterprise with all his old energy: he was well known and well liked: old friends elbowed their way across the bridge to him: and he had the South Side pretty much to himself.(*) The counter soon grew too short, and the little office in Carlton Place altogether too small. A new office had to be built, and the business of the Laurieston branch grew to be one which surprised everybody. From 1849 he served on the Town Council and from 1853-55 was instrumental in supporting Provost Robert Stewart’s proposal for a clean water supply for Glasgow from Loch Katrine. In 1850 he became a burgh magistrate.

James I married Jeanie Cleland with whom he spent forty years of a happy married life and who died very suddenly in 1870. He never got over the shock, and died eighteen months later at Bothwell, where he had gone to recruit. He left four daughters and one son, Robert Gourlay, Manager of the Bank of Scotland, Glasgow who spent his whole life with the bank and is buried in the Necropolis.

James Gourlay II (1869-1952) was Robert’s eldest son. He was educated at Kelvinside Academy and took a degree in Mechanical Engineering at Glasgow University. He worked for an engineering company at Polmadie in Glasgow and travelled in Europe selling pumps and other company products. He had put some money into the business but it failed and he recovered much less than he invested.

James Gourlay II (1869-1952) was Robert’s eldest son. He was educated at Kelvinside Academy and took a degree in Mechanical Engineering at Glasgow University. He worked for an engineering company at Polmadie in Glasgow and travelled in Europe selling pumps and other company products. He had put some money into the business but it failed and he recovered much less than he invested.

In 1896, James II, who was still living at his father’s home at 11 Crown Gardens, Dowanhill, married his cousin, Ella Moffat in Glasgow. She had been born and brought up in the United States and her father was a brother of Mary (Brown Hastings Gourlay) Moffat. There were three daughters from the marriage.

In the 1914-18 war James II became a Colonel in the Royal Engineers and after the war he became a company director of George Outram who published the “Glasgow Herald”. Directors then were appointed largely by family connection and his father Robert had been a director of George Outram previously. James was extremely fortunate in that shortly after he joined as a director in 1921, there was a major “burst up” within the board and among all the fighting, James II seems to have found favour with both sides and although he had only been with the company for a short time, he was made Chairman.

There is no doubt that after the old members departed, James II very astutely invited a collection of his friends to join him. This let him enjoy many years of loyal support which was of great benefit to him as it allowed him to remain as chairman until he was 80 years old and was so deaf that it was clear that he attended meetings and came away having heard not one word of what had been said. As well as director of the Outram Board, James II was also a director of the Bank of Scotland – again no doubt due to his family connections and in 1940 he was made Deputy Governor of the bank. His home from 1923 until he died was at Brankston House, Stonehouse, Lanarkshire.

Note by James Farquhar – I am not clear how Mary (Brown Hastings Gourlay) Moffat’s family was able to arrange for her burial in the Necropolis. Her husband at the time of her death was a bank manager and as far as I know there was no previous family connection with the Necropolis.

Glasgow Fire Memorial

Friday, March 11th, 2011Cheapside Street Fire

On 28th March 1960, a bonded warehouse in Cheapside St, Anderston, Glasgow, owned by Arbuckle, Smith & Co Ltd, went up in flames. Men from every division of the Glasgow Fire Service attended, even those who were not on duty that night, such was the dedication of those men. It was a fire the likes of which Glasgow had never seen and one which would live on in the memory of many Glaswegians to this very day. At its peak 450 fire fighters were engaged in fighting the blaze that was fuelled by more than a million gallons of whisky and rum, which sent fierce flames into the night sky, that could be seen for miles around.

In all 14 firemen and 5 salvage men were killed that night, when the walls of the warehouse blew out into Cheapside St and Warroch St as a result of an explosion within the building. Three fire appliances were also buried in the falling masonry. The fire actually took a week to put out.

A public funeral took place on Tuesday 5th April 1960, and the citizens of Glasgow lined the streets to pay their respects to these heroic men, and it was no exaggeration to say this city literally came to a standstill. A public fund in aid of the wives and children of those who lost their lives was launched by the Lord Provost and a final sum realised amounted to £187,360, of which a significant amount came from ordinary men, woman and children of Glasgow.

Kilbirnie Street Fire

On 25th August 1972, a fire started in the Sher Bros’ cash and carry textile warehouse in Kilbirnie Street, Glasgow. A fireman was trapped by the debris, and six of his colleagues brave and true formed a rescue party to search for him.

A blow out occurred and part of the roof fell on the rescuers. In total seven firemen died that night. Some 3,000 mourners, including an estimated 500 firemen attended the service in Glasgow Cathedral, and loudspeakers relayed the service to a further 2,000 outside, 14 lorry-loads of wreaths were received.

Again widows and children were left to mourn the husbands and fathers who never came home again.

Never let it be forgotten, the ultimate price, these firemen paid for their city, or the debt we owe to all our firemen who perform a public service we must never take for granted.

Robert Goodall

Tuesday, February 22nd, 2011Born in Leslie 28th May 1833 – Died in Glasgow 23rd November 1908

Robert Goodall was born in Leslie, Fife on 28th May 1833, the third son of Robert Goodall, stationer and his wife Ann Russell. Educated at the local school, young Robert joined his father in the family business before being “ferried” across the water to Edinburgh (his own words) to begin his apprenticeship in the paper trade in 1847. The thorough training which he received there gave him the foundation of a career which ultimately took him to Glasgow and the very front rank of his profession with the firm of William Collins & Sons. He travelled throughout Scotland, becoming one who was known, not just for his business skills, but also as one who would go out of his way to do a good turn or help a struggling workman or colleague.

In January 1908 a grand banquet was given in Robert Goodall’s honour, celebrating his Jubilee in the paper trade. The great and the good of the city of Glasgow were present to acknowledge, not just his contribution to the paper trade in Scotland, but also his support of the literary and cultural activities of “The second city of the Empire”.

Robert Goodall’s life was perhaps best summed up in a quote from the local paper, “The Leslie Globe” :-

“Mr Goodall had and extraordinary personality. To meet him was like having a ray of sunshine thrown across the path. Uniting an uncommonly fine physique to a most winsome manner and generous disposition, it was not surprising that when he presided at a Burns banquet in Glasgow that ministers, professors and members of Parliament , who graced the large company, were alternately swayed and inspired by the “Leslie laddie”, who, whether acting as the presiding genius or not, was himself the life and soul of every company he joined.”