Sergeant Samuel Ewing, R A

By Morag T Fyfe

It is probably not widely known that the Kingdom of Sardinia took part in the Crimean War (1854-1856) on the side of the Allies. An expeditionary force of 18000 men reached the Crimea in May 1855 from Genoa. At the end of the war Sardinia, like her allies, issued a Crimean War Medal (Al Valore Militare) and 450 specially selected officers and men of the British Army (400) and the Royal Navy (50) received the medal. Amongst 20 officers and men of the Royal Artillery who were awarded the medal was Sergeant Samuel Ewing, 7th Company, 11th Battalion, Royal Artillery. For his service in the Crimea he was also entitled to the British Crimea Medal and he was one of a select few to receive the French Médaille Militaire.

Samuel Ewing was born to Samuel Ewing senr and his wife Catherine in the autumn of 1830, the middle child in a family of five. He was most likely born in Ireland though other sources disagree. By 1841 he and his family were living in Glasgow and 14-year-old Samuel was working as a potter. When he enlisted as a Gunner and Driver in the Royal Artillery in May 1849 he also gave his trade as a potter. To enlist in the Royal Artillery a recruit had to be at least 5ft 7in tall as strong men were needed to work the guns. When the Crimean War started this requirement had to be lowered as it was hindering recruiting too much. By at least 1851 Samuel was serving in the 6th Company of the 11th Battalion of the Royal Artillery and he later transferred to the 7th Company of the same Battalion. For the first four years of a man’s service he was considered to be a recruit as he underwent the required training. The Royal Artillery did not use the term ‘private’ instead using the term ‘gunner and driver’. This illustrated the dual nature of the private soldier’s job in the Artillery – serving the guns and riding and driving the horses pulling the guns and ammunition waggons.

Most of Samuel’s service was spent in the United Kingdom (in 1851 he was at Chatham) but on 28 March 1854 Britain and France as allies of Turkey declared war on Russia and what became known as the Crimean War began. Both the 6th and 7th Companies of the 11th Battalion were amongst the original contingent assembled to go to Turkey’s aid and by the middle of July 1854 they had reached Varna in Bulgaria. The decision to invade the Crimea being made, the allied army started landing in the Crimea on 14th September 1854. Samuel was serving in the Siege Train and it was not disembarked at first though the men helped to land horses, guns, ammunition and stores for the field artillery.

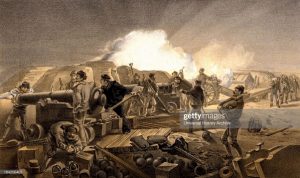

Less than a week after the allied invasion they faced the Russians at the battle of the Alma but it was not until the decision to invest Sebastopol was taken that the Siege Train was disembarked at Balaclava beginning on the 28th September. The Royal Engineers began to prepare sites for the besiegers’ guns facing the south side of Sebastopol on the 10th October and by the 16th the guns were in position and ready to open fire. The guns were grouped in batteries and although it is known that Samuel’s company was towards the right-hand side of the British line it is not known which battery he served in.

The Russians tried to stop the siege of Sebastopol and fought the French and British just outside Sebastopol at Inkerman. Most of the artillerymen engaged at the Battle of Inkerman belonged to batteries of the Royal Horse Artillery attached to the cavalry or were field batteries of light guns supporting the infantry but Lord Raglan, the commander in chief, asked for any available heavy guns to be despatched from the Siege Train to help and two 18 pounders were sent. These were under the command of Lt Col Dickson who, at that time, commanded the 7th Company in which Samuel served. When the British Crimea Medal was issued after the war with various clasps to mark which actions the individual took part in, the men of the 6th and 7th Companies, 11th Battalion were the only two companies amongst the siege companies entitled to that clasp.

‘A Hot Day in the Batteries’. Tinted lithograph after W Simpson for “Illustration of the War in the East” (London, 1855-1856). (Photo by: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

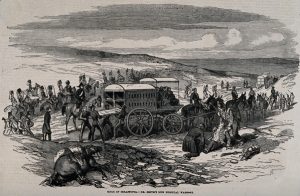

The winter of 1854/55 was very hard on the troops in the Crimea as they were very short of most provisions including warm clothing. Endemic disease and poor sanitation meant that by February 1855 almost half the army was on the sick list. Many of the artillery’s horses died for lack of fodder hindering the supply of ammunition to which sometimes had to be carried to the batteries by the men themselves – an iron ball for a 32-pounder gun weighed 32 pounds so a man could only carry one at a time.

In 1854 there were only six companies present in the Siege Train and losses had been heavy but eight companies of reinforcements arrived during the winter of 1854/55. Samuel continued to serve at the siege of Sebastopol taking part in the next three bombardments of the city on 9th April (Easter Monday in both Orthodox and Western churches that year), 6th June and 17th June 1855 respectively. Following the bombardment on the 6th June some of the Russian outworks were captured.

Following the bombardment of the 17th June the British launched an attack on the Redan in the early hours of 18th June. The attacking column was accompanied by twenty volunteers from the Royal Artillery who intended to spike the enemy guns or even turn them against the enemy if the opportunity arose. The attack was repulsed and eleven of the Artillery volunteers were killed or wounded including Bombardier Samuel Ewing whose left leg was severely damaged by a round shot.

Like so much of Samuel’s story one can only make an informed guess as to what happened to him after he was wounded. Doctors were present in the trenches but one presumes Samuel was soon moved to the General Hospital at Balaclava, possibly in one of the new hospital waggons.

He may then have been transferred to the main British hospital at Scutari near Constantinople. If so, he was lucky as Florence Nightingale had arrived at Scutari the previous autumn when word got back to Britain about the horrendous conditions for sick and injured soldiers there. It may be as a result of the improved hygiene and care that he not only survived six weeks of treatment of his injured leg but its subsequent amputation four inches below the knee.

Samuel’s promotion history seems rather unusual. His first step from Gunner and Driver to Bombardier occurred in August 1854 while the company was at Varna, Bulgaria just before it embarked for the Crimea. His promotion to Corporal took place on the 9th July three weeks after he was injured, while he was in hospital but before his leg was amputated. His promotion to Serjeant followed on 27th December 1855 when it must have been obvious that he was too badly disabled to remain in the Regiment and would have to be discharged, unless there was some thought that he could remain in the regiment in a clerical role. If this was the plan it came to nothing and Samuel was discharged with a pension of 1s 2d per day as an out-pensioner of the Royal Hospital, Chelsea.

Samuel returned to Glasgow to live with his widowed mother, Catherine, and an unmarried sister, also named Catherine. The three of them were found in the 1861 census living at Dunchattan Street just off Duke Street and close to the Necropolis. Two years later he had moved round the corner to Fisher Street and it was there that he died on 19th July 1863 having suffered from cancer of the stomach for two years. He was only thirty-two when he was buried in an unmarked grave in the Necropolis on 21st July 1863, the first Crimean veteran found during the present indexing project in the Necropolis.

Sources

The bulk of this biography is based on military records for Samuel Ewing found on Ancestry and Find my Past.

Colonel Julian R J Jocelyn’s book The History of the Royal Artillery (Crimean Period) published in 1911 supplied much useful background information.