François Foucart

Napoleon’s Knight in the Glasgow Necropolis

Contributed by Gary Nisbet. 2019 (revised 2023)

Introduction

It is not generally known that there is a veteran of Napoleon’s Grande Armée buried in the Glasgow Necropolis. This is François Joseph Foucart (1793-1862), who settled in Glasgow after the end of the Napoleonic Wars and became a celebrated fencing master and teacher of gymnastics at the Andersonian University, now the University of Strathclyde. His monument is in the cemetery’s Upsilon division and is a tall obelisk ornamented with a wreath from which a medal was suspended.

Foucart had served in Napoleon’s infantry and was a veteran of the Russian campaign of 1812 and the battles of Leipzig and Waterloo. At some point he was appointed a Knight of the légion d’honneur, which is represented by a finely carved replica of the medal on the front of the monument which stands over his grave in the Necropolis.

The wreath and légion d’honneur on François Foucart’s monument in the Glasgow Necropolis, carved by J. & G. Mossman, 1863.

Until recently little was known about his early life and his years in the army, and why he should have settled in Glasgow after the Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815. There is also, unfortunately, no surviving portrait of Foucart. However, we do have descriptions of him. According to his military records, by 1815 he was 5ft 7ins tall with chestnut hair and blue-grey eyes, an oval face and medium sized nose and mouth. He is later described as having a fine moustache and a strong and imposing physique. His later life is well documented due to the celebrity that his subsequent career with the sword accorded him. New information has come to light, however, which enables us to clarify and confirm many of the missing details from his early years, and to correct some of the erroneous information about him that is recorded in the dedicatory inscription on his monument.

The most important of these errors is his birth year, which is given as 1781, whereas his baptismal and military records confirm that he was born in 1793. The inscription also states that he was an officer in Napoleon’s Imperial Guard, when in fact the highest rank he held was that of sergeant. Despite its inaccuracies, it is clear from the dedicatory inscription, together with his own written recollections and military records, that Foucart was not only a man of great courage and determination to survive his military service and many wounds, but also to escape from the post-war persecution of Bonapartist sympathisers in France and flee to the United Kingdom as a political refugee.

It turns out that his decision to move to Scotland was an entirely happy one and he became a prosperous and much-loved character and contributor to the life of the city, and to the University of Strathclyde in particular, where he taught fencing and gymnastics in the 1830s (when it was known as the Andersonian University). After this he established a fencing school and gymnasium in West Nile Street and became celebrated in his day as one of the finest fencing masters in Scotland, and is recognised today as the ‘father of physical fitness in Glasgow’. But his story has a far greater dimension that links his family name, via his sons Auguste and Dr. Louis Foucart, and his granddaughter, Alice, to other important historic events at home and abroad.

Early life and military career

Foucart was born on in the fortress town of Valenciennes in the North of France, on 11 August 1793, the son of Louis Foucart, a former military officer, and his wife, Celestine Flamand. Initially working as a wheelwright, his military career began in 1808, when he volunteered as a teenager in the National Guard of the North, then entered the 44th Regiment of the Line as a corporal in 1809. He later transferred to the Walcheren Regiment (later 131st Regiment) as a sergeant in 1810, and eventually moved to the 22nd Regiment of the Imperial Guard in 1814. During this time, he fought in the siege of Flushing, where he received shrapnel wounds to his thighs, and followed Napoleon into Russia in 1812.

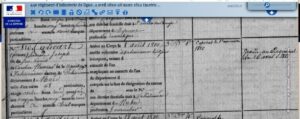

Foucart’s enlistment record for the 44th infantry regiment of the line in 1810. (Image courtesy of Mémoire des hommes (defense.gouv.fr)).

After surviving the epic retreat from Moscow, Foucart was present at the battles of Wurtzen, Bautzen, Jüterbog, and Leipzig, where, with the help of 40 grenadiers, he delayed the enemy at the Elster bridges and enabled Napoleon’s defeated army to escape annihilation and to return to France. It was for this action that he was cited for the Légion d’honneur and a field promotion, but he received neither until much later. He was also present at Napoleon’s final battles, at Ligny and Waterloo in Belgium in 1815, where he fought the Prussians as a sergeant of tirailleurs (skirmishers) in the Imperial Guard at the village of Plancenoit, and was wounded in the chest by a lance and shot in the leg. His wounds appear to have been slight, however, as he escaped the battlefield to take part in the defence of Valenciennes in the closing weeks of the war.

The medal on Foucart’s monument in the Necropolis. The medal has since disappeared from the monument.

A political refugee and professor of fencing and gymnastics

After Napoleon’s exile to St. Helena, Foucart became a sergeant in the 6th Regiment of the Royal Guard. However, after voicing his support for Bonaparte, he was imprisoned and sentenced to transportation to Cayenne in French Guyana. Before being sent there, he ‘broke the bars of [his] prison cell’ and escaped to Belgium and the Netherlands before crossing to England in 1816, as a refugee from political persecution. Settling in London, where he married a Belgian girl, Lambertine Leveille, who is buried beside hm in the Necropolis, he later moved to Dublin as a fencing teacher and then moved to Scotland around 1824, where he settled in Glasgow for the rest of his life and founded ‘The Glasgow Fencing, Gymnasium and Orthopaedia Institution’. He is listed in the Glasgow Post Office Directory as a fencing master for the first time in 1825.

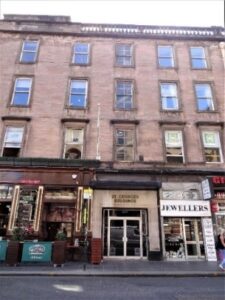

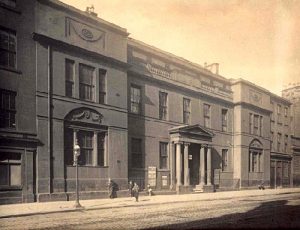

The old Andersonian University, George Steet. Its site is now occupied by Strathclyde University’s Royal College Building

![Champion Badge awarded by Foucart to his pupils. The initials MGFC stand for Member of the Glasgow Fencing Club. The badge belonged to Foucart’s son, Louis, and is inscribed: ‘L. Foucart [beat] G. Roland, 7 to 2. Champion Swordsman of Great Britain. Glasgow, May 1839.’ (Roland was the son of the Frenchman George Roland, a celebrated fencing instructor in Edinburgh. Roland and Foucart were the most important and influential teachers of fencing and gymnastics in Scotland in their day).](https://www.glasgownecropolis.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Champion-Badge-awarded-by-Foucart-to-his-pupils-300x224.jpg)

Champion Badge awarded by Foucart to his pupils. The initials MGFC stand for Member of the Glasgow Fencing Club. The badge belonged to Foucart’s son, Louis, and is inscribed: ‘L. Foucart [beat] G. Roland, 7 to 2. Champion Swordsman of Great Britain. Glasgow, May 1839.’ (Roland was the son of the Frenchman George Roland, a celebrated fencing instructor in Edinburgh. Roland and Foucart were the most important and influential teachers of fencing and gymnastics in Scotland in their day).

Around 1832 he became a professor of fencing and gymnastics in the Andersonian University, where he rented a large room for his classes in the Old Grammar School at 178 George Street (now the site of the present Royal College Building). Foucart is mentioned in the university’s Minute Book covering the period 1832-39, in which the matters concerning him were of a relatively trivial nature, such as arranging to have his gymnasium white-washed, the amount of rent he was required to pay for the room (£18 per annum, or £15 if he couldn’t afford the higher sum) and the number of pupils attending his classes in fencing and gymnastics. By 1837 they numbered 57 young men and women from the best families in Glasgow and the surrounding districts. He appears for the last time in the university’s records in February 1839, by which time he was involved in establishing a new fencing academy and gymnasium in the recently built Victoria Baths Building at 106 West Nile Street, which still stands today.

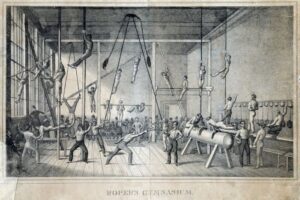

Roper’s gymnasium in Philadelphia, c.1831, which gives a good idea of the activities and equipment available in Foucart’s gymnasium at the Andersonian University.

(Image courtesy of The Library Company of Philadelphia).

This was a time when sword fencing was a much more popular sport than it is today, and when swordsmanship was regarded as an art to be taught as part of a young gentleman’s and young lady’s education. Foucart was particularly successful in popularising this branch of the martial arts and regularly held public demonstrations of his own and his pupils’ swordsmanship to great acclaim in the town’s Assembly Rooms in Ingram Street. These ‘assaults’ as they are called, always attracted ‘brilliant assemblages’ of fashionable society eager to be thrilled and entertained by Foucart’s skill with the rapier and sabre, and they were rarely disappointed by the spectacles he mounted. For the winner of his pupils’ assaults, a light sword donated by Foucart would be their prize. He also presented them with champion badges which would later be used as the model for the wreath and crossed sword carved on his monument in the Necropolis.

The press, too, were delighted by his displays, which became a highlight of the sporting calendar of both Glasgow and Edinburgh, and they reported enthusiastically on the events and the excitement they generated. The assault held for the anniversary meeting of Foucart’s pupils on 18 April 1829 was, according to The Glasgow Herald, ‘one of the finest ever witnessed’. In Edinburgh he participated in the annual assaults presented by Monsieur George Roland, another French émigré who established the finest fencing academy in the capital. In February 1830, Foucart and Roland’s duels mesmerised their audience, with Foucart being reported as giving ‘more reason than ever to admire his irresistible impetuosity’. Decades later, having become firmly established in the city and in the hearts of his pupils and friends, testimonials were presented to him in the form of a silver vase in 1847, and a silver cup in 1855. They also held annual dinners in his honour.

By then, with his business now a great success, and with his sons, Auguste and Louis, as partners and instructors, Foucart had been assiduously promoting the health-enhancing aspects of his work and introduced new equipment devised by his doctor son, Louis, with which to facilitate the results in improving bodily strength and alleviating physical infirmities in both sexes. In the Glasgow Herald of 29 October 1852, they announced:

‘Messrs Foucart have resumed their courses of practical instruction to ladies and gentlemen in the art of training and developing the human frame, and in preventing and correcting bodily distortions, and promoting health by their system of gymnastic exercises. Messrs Foucart have also much pleasure in announcing that they have added to their stock of apparatus, and will give instructions in proper the use of Dr [Louis] Foucart’s newly registered Spinal Rectifier and Chest Expander, which instrument has been patronised by the royal family, and received the approval and recommendation of the leading [London] surgeons. The institution is under the inspection of the most eminent of the medical profession in Glasgow.’

Foucart’s popularity amongst the higher echelons of Scottish society is best exemplified by his participation in the famous Eglinton Tournament of 1839. A spectacular recreation of medieval pageantry and jousting which involved the crème of Scottish knightly nobility as participants and spectators, as well as thousands of onlookers from the general public. Foucart would have been required to don medieval attire and give his best performance in the displays of swordsmanship that were intended to enthral his audience and remind them of the chivalric glories of ages long past.

Later life, family and Foucart’s death

Foucart must have been quite a character in his day, and he was certainly popular amongst his students and the public alike. Amongst his students were the poet William Motherwell and the dramatist James Sheridan Knowles, who modelled the hero of his play, Monsieur de l’ Épée on him in 1838 (both writers are also buried in the Necropolis). It is also claimed that he was the inspiration for the hero of Alexandre Dumas’ novel, Le maître d’armes, in 1840.

Foucart’s home at 4. Falkland Place, near St. George’s Cross, where he died in 1862. (Image courtesy of Glasgow City Archives).

Foucart’s life in Scotland was by all accounts happy and prosperous, and he was blessed with a long marriage and loving family. He and his Belgian-born wife, Lambertine Levelly (1791-1877), were married in London, in the church of St John the Evangelist, Westminster, on 26 July 1818. They had at least four children: Louis, who was born in France during a brief return to Foucart’s homeland in 1820; Virginie and Mélenie, both of whom were born in Ireland; and Auguste, who was born in Glasgow in 1833, and who followed his father’s profession as a fencing master and gymnastics teacher.

The family lived at various addresses in central Glasgow. As early as 1826, the Foucarts lived in a ‘Cottage Style’ house on the east side of Portland Street. The house and garden were put up for sale and advertised as ‘admirably adapted for building’ in the ‘Subjects To Be Sold’ section of The Glasgow Herald for 1 May 1826. Long since vanished, the house and land were presumably redeveloped soon after they were sold.

The Foucarts then moved to 239 George Street, where they lived throughout the 1830s. They later moved to 5 St Vincent Place, St. Georges Buildings, staying there for a decade from 1842 (the building still survives). At this time the family home also doubled as a doctor’s surgery, which was run by Foucart’s son, Louis, who had recently graduated in medicine and surgery at Glasgow University. The census returns for the street in 1851 reveal that they were wealthy enough to employ a live-in house servant, Sarah Stewart. After Louis left home to practice medicine in London, the family moved house again and finally settled down at 4 Falkland Place, St George’s Road, in 1853.

François Foucart died at his home on 26 June 1862, of acute bronchitis, which he had suffered for about a month. He was buried in the Glasgow Necropolis at 2pm on 1 July, in lair 60 of the cemetery’s Petra section (now Upsilon), which was purchased for £16; the funeral being undertaken by Wylie & Lochhead.

Foucart’s last Will and Testament of 7 March 1862 offers evidence of his prosperity. To his beloved wife he left £5,557.9d (£864,472.93 in today’s money), the value of which included shares in the Clydesdale Bank, the Bank of Scotland and the Glasgow Gas Company, as well as a collection of silver plate. A year later, in 1863, the high esteem in which he was held amongst his friends and former pupils was attested to when they erected the monument that stands over his grave today. This was produced by J. & G. Mossman, the celebrated Glasgow-based firm of monumental and architectural sculptors. It is in the form of an obelisk, 15 feet tall (4.57m). As well as the carving of Foucart’s légion d’honneur on its front, a long eulogy was inscribed on the shaft of the obelisk, composed by James Sheridan Knowles and taken from his play Monsieur de l’Épée:

‘Talk you of scars? – That Frenchman bears a crown!

Body and limb his vouchers palpable;

For many a thicket he has struggled through

Of briery danger, wondering that he

Came off with even life, when right and left

His mates dropp’d thick beside him. A true man,

His rations with his master gone – for he

Was honor’s soldier, that ne’er changes sides.

He left his country for a foreign one

To teach his gallant art, and earn a home.

I knew him to be honest, generous,

High soul’d, and modest, every way a grace

To the fine martial race from whence he sprang.’

The dedicatory inscription recording Foucart’s personal details on the obelisk’s pedestal was almost as effusive as the eulogy cut on its shaft. This, however, has been completely obliterated by the passage of time and the elements. Thanks to an account of the monument which appeared in The Glasgow Herald on Wednesday, 24 June 1863, soon after it was erected, we know the inscription’s exact wording:

Francois Foucart,

Born At Valenciennes, 1781.

Died At Glasgow, 1862.

An Officer In The Imperial Guard Of France

During The First Empire,

Knight Of The Legion Of Honour,

Professor Of Fencing, Royal Academy, Paris,

And Afterwards For Forty Years In This City.

This Monument Has Been Erected

By Some Of His Pupils, To Mark The

Friendship They

Entertained For Him,

And To Designate The Spot Where The

Remains Of A

Brave And Gallant Soldier Rest.

1863.

Foucart’s influential family

This was not, however, the end of Foucart’s enterprise in promoting health and fitness, or the fame garnered to his family’s name. His son, Auguste, later left the city to set up gymnasiums in Liverpool, Inverness, Greenock and Sydney in Australia, where his brother, Louis, had set up as a doctor. Louis, having already established his medical credentials in Scotland, later moved to London, where he became indelibly linked to the life and death of one of Britain’s greatest Prime Ministers, Sir Robert Peel. His association with him was brief, however, but of the utmost importance and renown, as it was Louis who happened to be close-by when Peel was thrown from his horse and very badly injured on the evening of 29 June 1850. He attended to Sir Robert until he died of his injuries in the evening of 2 July.

Later on, Louis Foucart moved to Sydney, Australia, where he became the Government Medical Officer of Health and Quarantine Officer at Port Jackson (now Sydney Harbour). He lived in Rozelle, and owned land in the appropriately named district of Waterloo. He eventually retired to England, where he died at Lucan House in Ripon, Yorkshire, on 25 March 1899. Before this, however, Louis’ daughter, Alice, had married the son of Colonel Henry Pulleine, who has gone down in history as being responsible for the worst defeat of a modern British army at the hands of spear wielding warriors at the Battle of Isandlwana in the Zulu War of 1879.

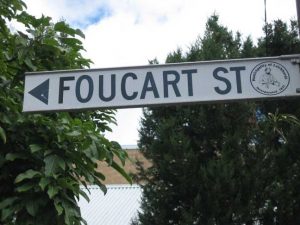

Back in Australia, it was Louis who was responsible for notices of his father’s death appearing in Australian newspapers in 1862, such as The Sydney Morning Herald and The Argus in Melbourne. This meant that François Foucart became as well known in the Southern Hemisphere as he was in Scotland at the time of his death. There is even a Foucart Street and Foucart Lane in Sydney. Although these were named after Louis, they also continue the association with his father and the great era of Napoleon and his Knight who rests thousands of miles away in the Glasgow Necropolis.

Foucart Street sign, Sydney, Australia, commemorating Louis Foucart. (Image courtesy of Rod Tacey)

Foucart’s descendants and his reputation today

Until recently, François Foucart had been completely forgotten in France and Scotland until this research into his military service and later teaching career was undertaken. This has been greatly assisted by Foucart’s own descendants, Peter Eden and his family, who live in Marvao, Portugal, and who are the guardians of not only the memory of their illustrious forebear, but also of many of his surviving personal items, such as his Légion d’honneur, and a sword that Napoleon is said to have owned and presented to Foucart for saving the life of Marshal Ney during the retreat from Moscow. They also have Foucart’s fob watch and the silver cup that his pupils in Glasgow presented to him as a testimonial to his popularity as a fencing master and as an individual.

The first of two silver testimonials presented to Foucart by his pupils and friends in the Glasgow Fencing Club. A vase, it was presented to him in 1847.

Of great importance amongst these personal items is the draft of a letter which Foucart sent to Napoleon III in 1852, which details his military career in his own words and, surprisingly, includes a request for the sergeant’s back pay that had been owed him from his time in Russia forty years earlier. The letter is the closest thing we have by way of a written memoir of his time serving under Napoleon I, and its contents are certainly of great value in illuminating hitherto unrecorded incidents during and after the war as experienced by one of its forgotten protagonists. It is especially enlightening with regard to the treatment of the emperor’s supporters by the French royalists after Waterloo and their later rehabilitation in 1820, when they were pardoned by royal decree on the birth of the Duke of Bordeaux.

The Eden family in Marvao, Portugal, descendants of Francois and Louis Foucart, and custodians of their personal effects.

It is clear from the letter, however, that Foucart was able to lead the rest of his life as a free man in Glasgow, where many other refugees from persecution have since been welcomed and encouraged, like him, to settle and prosper in safety. In France, for which he was prepared to risk his life in countless battles in the service of his beloved emperor, Foucart has now been accorded a biographical entry in the esteemed Guide Napoléon for the first time, where he is once again reunited with his former comrades in arms in the annals of French Napoleonic history.

In Scotland, where he settled and flourished in the land of his former foes, Foucart is also now becoming better known as a historical figure in his own right, and might now be described as ‘the most fascinating Frenchman who ever settled in Glasgow’, as well as the ‘father of physical fitness’ in the city. In addition to this, it is to be hoped that his connection to the University of Strathclyde in particular, will someday be commemorated by a plaque erected to his memory and sporting achievements in the university’s new sports centre in Cathedral Street.

Sources :

Archives de Valenciennes: Baptisms, François Joseph Foucart, Valenciennes, St Jean, 11 August 1793.

Cottin, Paul (ed.): Memoirs of Sergeant Bourgogne 1812-1813, New York, 1899.

Martinien, A., Tableaux, par Corp et par Batailles, des Officiers Tués et Blessé pendant Les Guerres de L’Empire (1805-1817), p. 441.

Sydney Morning Herald: Sydney Gymnasium, Thursday, 6 May 1861, p. 5.

Mitchell Library: Glasgow Post Office Directory, 1825-1867.

Strathclyde University Archives: SUA: OB/1/1/4, Andersonian University Minute Book 1830-1894, pp.41-222.

The Glasgow Herald: Fencing and Gymnastics, 28 September 1827. pp. 11.

Scotland’s People Death Print, RD: 644-06, Register of Death (François Foucart), No. 263, p. 88.

Mitchell Library, TMH32/5/2: Glasgow Necropolis Internment Notice Book, 1 July 1862.

Mitchell Library: Glasgow Necropolis Burial Register, 1859-1897, Microfilm, Spool 2.

Scotland’s People: Wills and Testaments, SC3, Confirmations, 216-217 and 610-61.

Black, James: The Glasgow Graveyard Guide, Edinburgh, 1992, Necropolis, No. 12, p. 45.

Sydney Morning Herald: Family Notices, Saturday, 23 August 1862, p. 1.

The Argus (Melbourne, Victoria): Deaths, Thursday, 4 September 1862, p. 4.

Johnston, Ruth, Glasgow Necropolis Afterlives, Glasgow, 2007, rev. 2020, p. 117 (ill.).

Morag Fyfe (Archivist, Friends of Glasgow Necropolis).

Information from Maryse Boudard (Archives de Valenciennes).

Information from Peter Eden (Descendant of François Foucart).

Information from Caroline Gerard (Genealogist, Friends of Warriston Cemetery, Edinburgh).

Information from Dominic Timmermans (Monuments Napoléoniens).

Information from David Peletier (Monuments Napoléoniens).

Roper’s Gymnasium Image: The Library Company of Philadelphia – America’s oldest cultural institution, founded by Benjamin Franklin in 1731.