Written by Morag T. Fyfe

Since Grave Matters 2 was produced indexing the burial registers has slowed a little due to various computer problems and holidays. Nonetheless there have still been a number of interesting discoveries made.

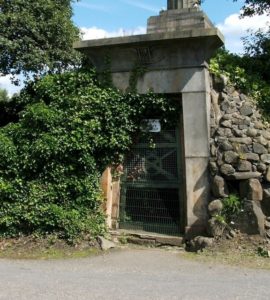

Egyptian Vaults

In Grave Matters 1 I briefly mentioned the Egyptian Vaults (shown above before their recent restoration) in which the coffin of Major Archibald Monteath was stored until his monument was ready. The Egyptian Vaults have a T shaped groundplan with a passage leading in from the entrance and short cross passages at the inner end forming the head of the T. Looking through the gate it is possible to make out the lifting rings for the individual vaults set into the floor. From the burial registers there is evidence that there were at least nine individual vaults available though the number of the vault used is not always specified in the burial register. Between 1838 and 1843 the vaults were used 38 times. They were still in use in 1862 but I don’t yet know when their use ceased.

One of the indexers was intrigued by an unusual name when he came across the burial of Alexis Snodgrass Papillon on 21st December 1842. Subsequently I referred him to the Jamieson/Papillon profile on our website for more information and he spotted a discrepancy in Alexis’s given age.

The burial register records Alexis’s age as 35 while the grave stone says 33; so which is right? It is not uncommon for ages on the stone and in the burial register to vary and there can be a number of reasons why this is so.

Papillion Grave

First of all it needs to be borne in mind that before 1855 there are no birth certificates as we know them; most people were baptised and their baptisms were hopefully recorded in the church’s baptismal register, and sometimes their actual date of birth might also be recorded. I do not think it was usual for most parents to obtain a copy of the baptismal entry from the minister so persons did not usually have written evidence of when they were born to allow them to calculate their age.

From the Old Parish Registers for Glasgow parish we know that Alexis was baptised on 10th December 1806 which implies she was born November/December 1806 (though that may be a misleading assumption to make). However let us assume, for the sake of argument, that she was born on 9th December 1806. This would have made her 36 years and 6 days old when she died on 15th December 1842 and means that neither her age in the burial register nor her age on the stone is correct.

Her burial was organized by her brother J P Jamieson and her mother was still alive in 1842, so Alexis’s date of birth and exact age ought to have been known to them. The fact that her age is a year out in the burial register suggests one of two things to me – either in the fraught days leading up to her death that year her December birthday was overlooked, or the year of her birth was misremembered and it was thought she had had her 35th birthday that year instead of her 36th.

Turning to the discrepancy on the gravestone, it will be noticed that the first name on the stone is that of J P Jamieson who died in 1869. The fact that his is the first name suggests the stone was not erected until after his death. Was there a temporary grave marker there before? As Jamieson was the last surviving member of his family in Glasgow it seems likely that the stone was erected by his executors and I wonder how much they knew about his sister, who had been dead for twenty seven years? So, all in all, it doesn’t surprise me that Alexis’s age on the stone is wrong.

Amongst the familiar causes of death that have been recorded a couple of more unusual ones stand out. On the 29th September 1843 William Murdoch a 20 year old tailor was buried and his cause of death was given as yellow fever. Four days later, on 3rd October the burial of another tailor, Charles Cranner, who also died of yellow fever was recorded. Considering yellow fever is a mosquito borne disease found in Central America, the Caribbean and sub-Saharan Africa the chances of William Murdoch and Charles Cranner contracting it in Glasgow seem extremely unlikely. It makes one wonder what they did die of that could be mistaken for yellow fever.

Another young man who met an untimely end was William Muir a 23 year old painter who was buried on 24th March 1842. His cause of death was very informative as it said ‘accident from explosion of boiler on board Telegraph steamer at Helensburgh’. This was the second time the victim of a steam ship explosion was buried in the Necropolis. In 1835 the boiler of the Earl Grey steamer blew up when she was alongside at Greenock killing six people and severely injuring fifteen. One of the injured, Ebenezer Bell, later died from his injuries and was buried in the Necropolis.

The Telegraph was a wooden paddle steamer built by Hedderwick & Rankin in 1841 for the Glasgow-Helensburgh service. She was lightly built for speed with an experimental high-pressure engine in order to compete with the railway. On the 21st March she had just disembarked some passengers at Helensburgh and was backing away from the quay to proceed to Gareloch when her boiler violently exploded. The force of the explosion completely shattered the hull and threw the engine and boiler, which were combined into one piece and weighed 8 tons, 100 feet from the ship. Sixteen people were killed immediately and about fifteen seriously injured while the final death toll reached twenty.

William Muir was one of a group of six or eight painters (reports vary) travelling to Gareloch to work on the painting of a new ship launched by Hedderwick and Rankin in October 1841 called Precursor (below). Precursor was a completely different type of vessel to Telegraph, the river steamer. Her first owner was the Eastern Steam Navigation Co and she plied the Suez-Calcutta route until she was withdrawn in 1858. Another passenger travelling to Gareloch was Peter Hedderwick partner in Hedderwick & Rankin who also lost his life that day.

Precursor

I recently came across the burial of a little boy called Arthur Welesley Watson and I immediately wondered why he was named after the Duke of Wellington. Judging by young Arthur’s age at death he had been born in May 1842. By this date Wellington was an old man though he did not retire from political life until 1846 and it is difficult to imagine what caused a Glasgow father to name his son after Wellington by then. On checking the database I found we also had an Arthur Wellesley Ritchie (c1854-1879).

I then started to wonder about other children with famous or unusual forenames. From 1851 to 1872 the minister of the Barony Church was the Rev Dr Norman Macleod and five men buried in the Necropolis bear these forenames. It is impossible to prove that they are named after the minister but both Norman Macleod Stewart (1853-1854) and Norman Macleod Crawford (1872-1873) were born during Macleod’s ministry in the Barony.

One of the men for whom I feel most sorry is Primrose Bell, a Glasgow merchant who died in 1841 aged 76. It wasn’t uncommon for a younger boy in the family to be given his mother’s maiden name at baptism which is presumably what happened here.

Some unusual names are also found amongst the women. In their case one finds feminized versions of male names like Angusina Margaret Mcdonald (c1905-1970) daughter of John Mcdonald and Margaret Mcleod and Gavina Norie Paterson (1861-1880) daughter of Gavin Paterson and Annie Muirhead. Girls were also given surnames as forenames. Mrs Mathieson (c1880-1918) was born Connel Mary Cargill daughter of David Cargill and Connel Auld and grand daughter of William Auld and Connel Simpson. Unusual forenames like Connel are a godsend to family historians.

We recently received an enquiry from an author about whether it was likely that a couple who died in the 1960s would be buried in the Necropolis. Thanks to the indexer working on the 1960s burial registers I was able to reply that it was possible to be buried in the Necropolis at that period but I queried whether it was likely. The 1960s registers normal recorded whether a burial was taking place in a newly purchased lair or not and, as the addresses of the deceased were recorded, it is possible to get a picture of who was buying a lair in the Necropolis at that time; generally it was local families from Dennistoun and Townhead. Most of the lairs sold were in compartments Quartus or Secundus both in the lower quarry area.

Quartus

One of our volunteers recently took a Canadian lady on a tour of the Necropolis looking in particular for any Masonic gravestones. This is not a topic about which we know very much and we would be grateful for any help in identifying possible Masonic gravestones.

Some new profiles have been added to our collection: Rev Robert Cunningham (1799-1883), William Graham (1817-1885), Alexander Mackenzie (d. 1875) and his cast iron monument and Sir David Richmond (1843-1908).

******************************

Anyone who would like to help with this indexing project is very welcome to join us by contacting me at research@glasgownecropolis.org